I’m only focusing on one issue this week, simply because it’s so staggeringly bad and I think has eclipsed everything else that happened this week.

If you’ve been forwarded this newsletter, click here to subscribe and get updates sent to your inbox every Saturday morning. If you have any feedback, just hit reply!

It’s time to talk about data privacy again

Pardon my French, but whaaaaat a shitshow its been this week in terms of data privacy in Singapore.

On 28 January, the Ministry of Health revealed that personal data—including names, ID numbers, phone numbers and addresses, among others—of a whopping 14,200 people living with HIV (PLHIV) had been leaked online. The data of another 2,400 who had been contacts of PLHIV have also been disclosed online.

This is utterly horrifying news, because PLHIV already have to battle stigma and discrimination in Singapore. There is very good reason why PLHIV often choose not to be public with their status: there are genuine concerns over getting fired, being rejected by family and friends, getting trouble from insurance companies, etc. There are repercussions that those of us who aren’t affected by this leak cannot even possibly begin to imagine. It is highly possible, for instance, that this catastrophe will set back efforts to educate people and encourage them to get tested or seek access to healthcare.

The government says the leak came from Mikhy K Farrera-Brochez, an American who was the partner of Ler Teck Siang, who in turn headed the ministry’s National Public Health Unit from March 2012 to May 2013. Farrera-Brochez had been convicted of fraud and drug offences in 2017—the fraud charges had to do with faking the results of his HIV test by using Ler’s blood instead. Ler is also in hot soup; he was charged with offences under the Penal Code and the Official Secrets Act in 2016, and was convicted in 2018 of abetting Farrera-Brochez to commit cheating, as well as providing false information to the authorities. (His appeal’s coming up.) On top of that he’s also been charged with the Official Secrets Act for “failing to take reasonable care of confidential information regarding HIV-positive patients”.

A lot of attention is now being lavished on the details of Farrera-Brochez and Ler’s relationship—which is not only missing the point, but likely adding to the stigma against LGBT people in Singapore. What I’m much more interested in is questions related to accountability and the wisdom of data collection.

When the Ministry of Health pointed the finger at Farrera-Brochez, they revealed that they’d known since 2016 that he was illegally in possession of the information. Which of course led to the not unreasonable question of “why the hell didn’t you say anything then?!” Some commentators told TODAY that the government should have come clean once they knew the sensitive information had been accessed without authorisation. After all, the government hadn’t waited until the information was leaked before informing the public that 1.5 million Singaporeans’ non-medical information had been stolen in the SingHealth data breach (that happened not that long ago).

There are more questions, including one that I feel hasn’t been asked often and persistently enough throughout the coverage so far: why did Ler have access to the personal details of PLHIV in Singapore, and why had he been able to copy the information on to the thumb drive? He might have been the head of the public health unit, but that doesn’t mean that he needs such granular detail about PLHIV. It’s not like he needs the phone numbers of specific individuals to be able to formulate public health policy, so why had there not been more compartmentalisation of data, so as to prevent this sort of horror story?

The ministry brought in safeguards in 2016 after they realised what had happened, so the system is at least better now, but it’s still worth asking why it had to take a screw-up like this before they realised that the system needed more levels of protection. And if this is how they got caught out with the safety of a really sensitive registry (another question: should Singapore even have a HIV registry?), then how safe do we feel about ideas like the national centralised medical database that the government is so keen to introduce in Singapore?

14,200 is a massive number, but many of us are lucky enough not to have to deal with the trauma, the fear, the anxiety. That said, this should be a wake-up call for all of us—instead of just letting the government say “sorry” and move on, this should be a moment for us to pay more attention the huge amounts of data that the government is keen to collect about us, and to ask: who is handling this, and how? And why should we even have over all this information to the government, anyhow?

Events and announcements

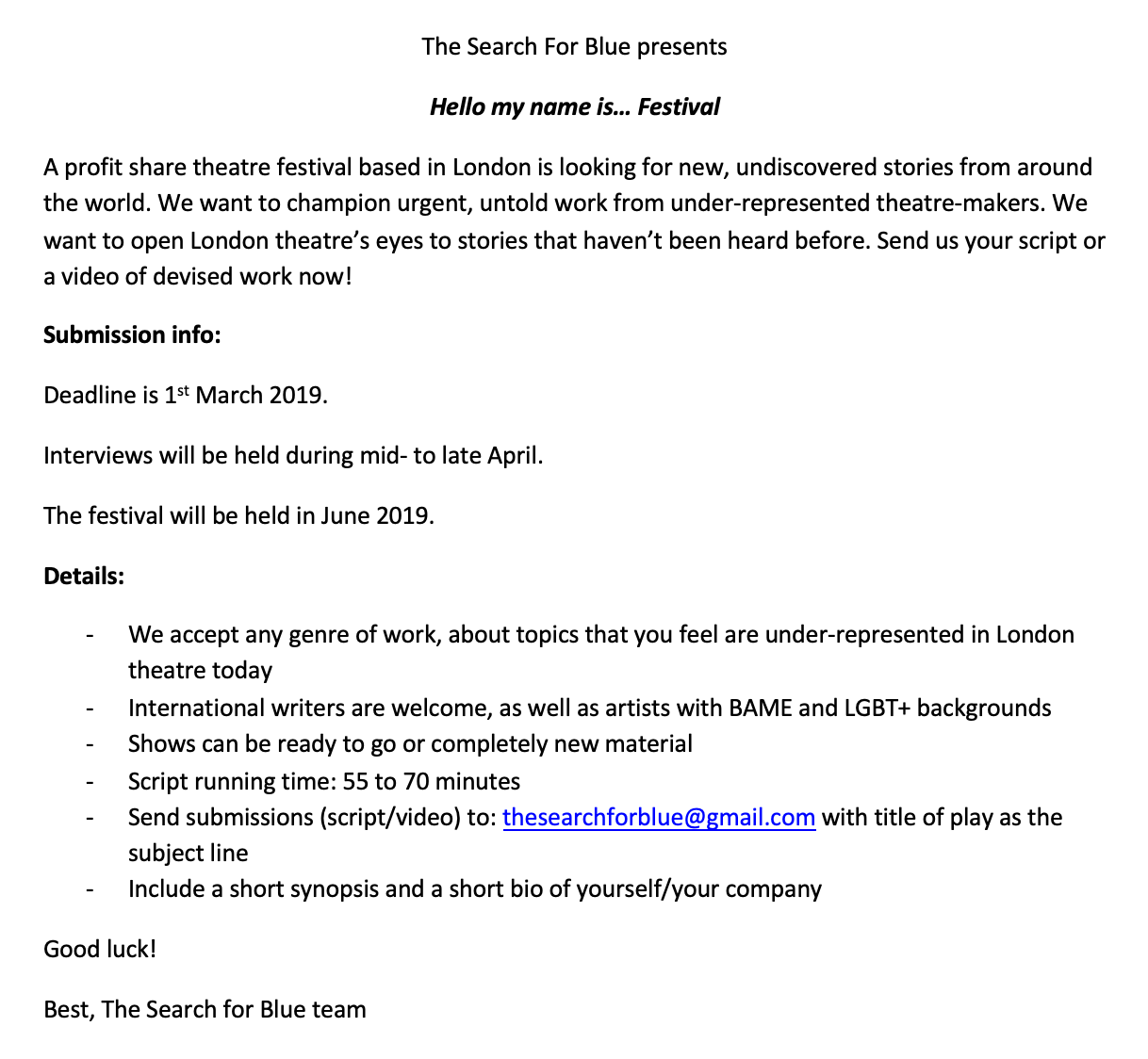

For theatre practitioners out there, here’s a little call for submissions from London:

About the neighbours…

We’re gearing up to celebrate the Lunar New Year in Singapore, but for decades in Indonesia Chinese Indonesians weren’t allowed to celebrate the festival. They were also made to adopt Indonesian-sounding names. Iskandar Salim examines names, culture, politics, and identity in his comic for New Naratif.