I’ve been an anti-death penalty activist for 10 years. In this time, I’ve tried my best to observe and document the application of capital punishment in Singapore, and to support the families of death row inmates as they navigate the system. When people ask me about this work, I tell them that one of the most horrifying things about the death penalty is how utterly administrative it all is.

There’s no better case to illustrate this clinical cruelty than what’s happening with Nagaenthran K Dharmalingam and his family right now.

In a letter dated 26 October, Nagaenthran’s family received the worst news: the Singaporean authorities had scheduled his execution for 10 November, just a little over two weeks away. “We will facilitate extended visits with him on a daily basis… until 9 November 2021 (Tuesday),” read a letter, from the Singapore Prison Service, addressed to his mother. “Please contact the officers listed in paragraph 12 to let them know if you and/or your family members will be travelling to Singapore to visit your son.”

Nagaenthran’s family live in Malaysia. Although Singapore has launched Vaccinated Travel Lanes (VTL) with multiple countries, allowing fully vaccinated individuals to travel without having to quarantine, there is no such arrangement with our neighbour to the north. The notice of Nagaenthran’s execution thus came with pages of Covid-19 travel guidelines and requirements.

On 28 October, I was put in touch with Sharmila, one of Nagaenthran’s sisters. As if having to deal with news of her brother’s imminent execution wasn’t enough, she was overwhelmed by all the rules for pandemic travel. When I asked if I could take a look at the full letter from the prison, she sent me photos of 10 pages — most to do with Singapore’s Covid-19 requirements for travellers.

This is how things will go for the family to come to Singapore to see Nagaenthran before his scheduled execution:

- They first have to figure out who in the family will be able to travel to Singapore (the prison said that they can facilitate travel and stay for up to five people), which involves working out who’s able to apply for leave from work at short notice. They also have to make sure that anyone who travels is fully vaccinated (which, thankfully, they are).

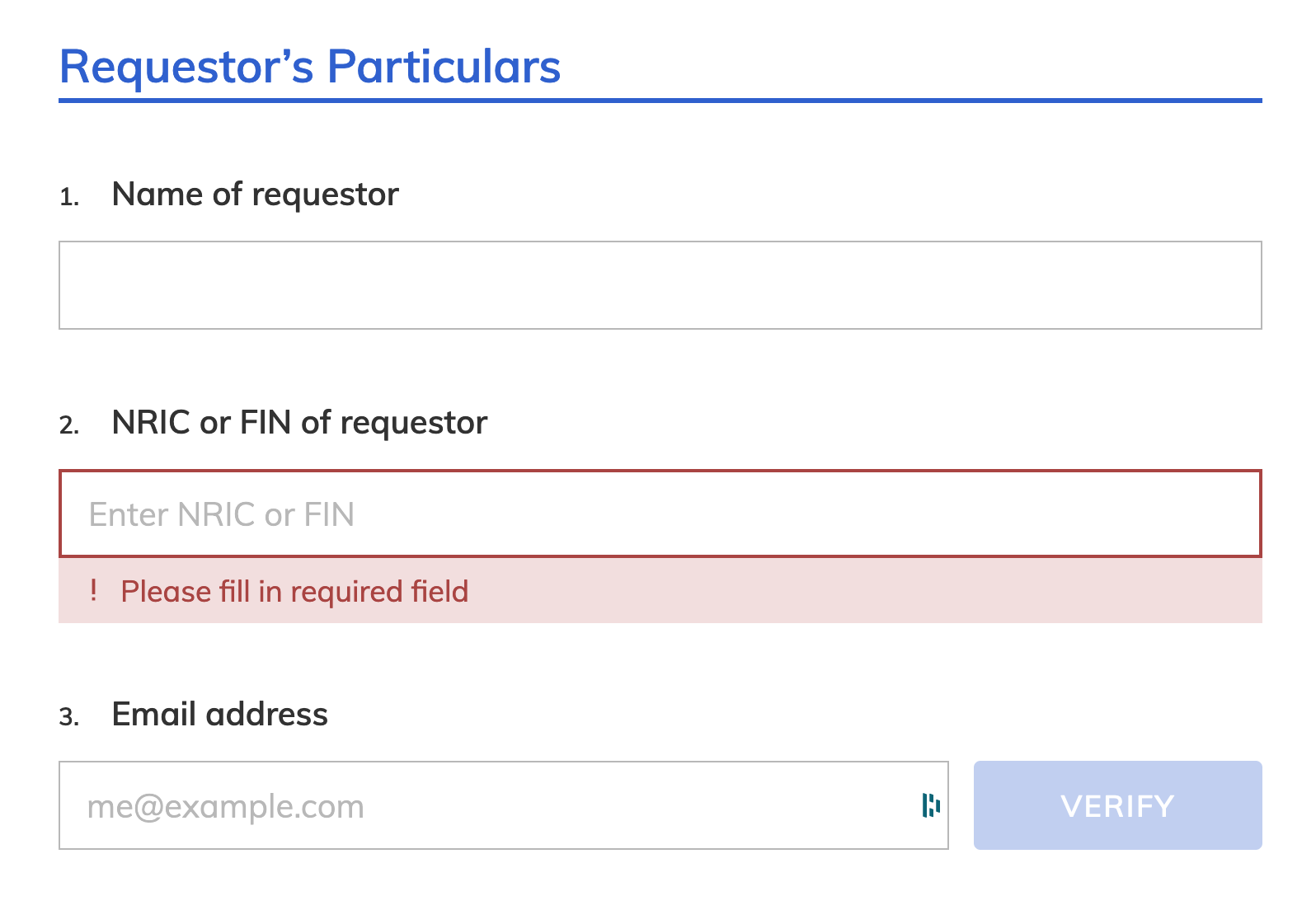

- Once decided on a travel date, they have to apply for entry approval via an online form. There needs to be one form per traveller.

- Once the entry approval application is submitted, they have to inform the prison officer right away. (I assume that this is so that the prison officer can make sure that the application is prioritised and approved.)

- Once entry approval is granted, they have to pre-pay for the PCR test that they will have to take in Singapore before they leave. It costs $125 per person.

- They have to book return flights (or whichever method of travel they might prefer) from Malaysia to Singapore.

- Once their flight is booked, they have to fill a health declaration form via the Immigration and Checkpoints Authority’s SG Arrival Card e-Service. This declaration has to be made not more than three days before travel.

- They will also have to do a pre-departure Covid-19 PCR test at an approved facility in Malaysia, not more than 48 hours before travel.

- They have to buy travel insurance, just in case they test positive for Covid-19 while in Singapore and end up having to get treatment or recover in isolation here.

- They have to find and book accommodation from a list of hotels approved to cater to people who have to serve Stay-Home-Notices (SHN). Under Singapore’s current Covid-19 rules, travellers from Malaysia are required to serve a 10-day SHN. They will have to pay for this accommodation themselves.

- They have to download and activate TraceTogether on their phones. If their phones are not compatible with TraceTogether, they will have to put down a $50 deposit (per person) to get TraceTogether tokens at the airport for the duration of their stay in Singapore.

- Once in Singapore, they will need to arrange their own transport from the airport to the hotel where they are doing their SHN. Due to the tight timeline, they will be under SHN conditions during their entire stay in Singapore.

- While here, they have to do an antigen rapid test (ART) for Covid-19 every day. If the result is negative, they will be granted an exception from regular SHN rules so that they can go to the prison to visit Nagaenthran from 10am–12pm and 2pm–4pm every day until 9 November. They can only go straight from the hotel to the prison, and back again. They will not be allowed to go anywhere else, nor meet anyone else.

- Since they are “strictly prohibited” from taking public transport during this time, they will have to figure out, and pay for, their own SHN-approved transport to and from prison.

- They will also have to figure out their own meals and get them delivered, since they won’t be able to leave their SHN accommodation.

- If the execution does take place — which, barring a miracle, it will — they need to have funeral arrangements sorted out. This means having an undertaker to deal with all the procedures necessary to repatriate Nagaenthran so he can be buried back home.

- Once back in Malaysia, they will have to adhere to Malaysia’s Covid-19 travel rules: from those entering Malaysia from Singapore, a seven-day home quarantine is required.

Even just on the face of it, this is a lot to deal with — especially when people are already upset and stressed out by the knowledge that their loved one is going to be hanged. But within each step can come other complications: for instance, when I rang hotels this morning, I found that many of the SHN rooms were already fully booked. Some of the staff, trying to be helpful, would tell me that they had vacancies from the 7th of November, or the 12th of November, implying that perhaps travel plans could be revised. But that isn’t an option for Nagaenthran’s family; they’re already running out of time. I called 10 hotels before I found one that could accommodate Nagaenthran’s brother when he arrives on Monday, ahead of the rest of the family coming in over the next week.

Nagaenthran’s family could never have navigated all this themselves. I’m not saying this to inflate my, or anyone else’s, importance. I mean they literally could not have sorted all this out by themselves. The entry approval application form, for example, required a “requestor” with a National Registration Identification Card (NRIC) or Foreign Identification Number (FIN), which none of the family have, since they are neither Singaporeans, nor holders of long-term visas for Singapore. (I ended up having to put myself down as requestor on their behalf.)

There are also things that, while not disastrous, just add extra steps to an already mind-boggling array of tasks. The letter from the prison provided the contact details of two officers, assuring the family that they would “try to guide and assist you with the arrangements as far as they can”. Since I’ve been handling almost all these arrangements for the family, Sharmila gave me the number of one of these officers. I also emailed them, cc-ing Sharmila, introducing myself as someone helping the family during this time, and asking some questions about what the prison can or can’t facilitate, so I can have a better idea of what we will need to prep for their stay in Singapore, and what might already be taken care of.

I didn’t get a reply to my email, and my WhatsApp texts were left on read. The prison officer told Sharmila that they will only speak to family members. They gave Sharmila answers to my questions, which she then relayed to me. Although I was the “requestor” who put down my NRIC and email address to apply for entry approval on behalf of Sharmila’s brother, the response was emailed to Sharmila instead — she then had to forward me the email, so I could click on the link to pre-pay for his PCR test. It wasn’t that big a deal, but seemed counter-productive when the whole point of me helping out was to reduce the amount of matters on Sharmila’s plate. It also made me wonder: if the prison service doesn’t like that someone is helping the family with all these arrangements, why not handle these things themselves? Yet, when I asked if the prison service could facilitate SHN transport to and from the prison, their response (to Sharmila) was that transport has to be arranged by the family.

Then there’s the issue of cost. The 10-day SHN hotel room for Nagaenthran’s younger brother alone cost almost S$2,000, or about RM6,200. Add in all the other costs of flights, accommodation, food, transport, and the funeral arrangements, and we’re looking at perhaps somewhere in the vicinity of S$10,000. Nagaenthran’s family wouldn’t have been able to afford this; when I spoke to Sharmila, she told me that various family members initially considered opting out of coming to Singapore — even if it would likely be their last chance to meet Nagaenthran — because they were worried about how they would pay for it all. It was only after I assured her that we could help them cover costs that the family decided that perhaps four or five of them would come down.

Luckily, people have been kind and generous. I put up a crowdfunding call for support on Friday afternoon; within 24 hours, we raised over $17,000. It was far more than the goal I had in mind, and has actually come as a relief, since things are costing more than I’d expected.

All this admin and bureaucracy needs to be done, and done in such a rush, for no other reason than the fact that the Singaporean state has decided that it wants to execute someone now. This is what abolitionists mean when we say that there is no murder more pre-meditated than capital punishment; what could be more pre-planned than a killing announced via an official letter accompanied by nine pages of procedural guidelines?

Usually, at this desperate juncture of a capital case, I’d be thinking about human rights standards and advocacy messages, and talking to the family about how comfortable they might be with public campaigning. This time, all the conversations I’ve had with Sharmila have been about passports and forms and vaccination certificates and travel itineraries; the need to get all the logistics sorted out, as quickly as possible, has crowded out opportunities and headspace for deeper discussions about the problems and issues.

Yet there are issues, beginning with the fact that Nagaenthran was found by experts to have borderline intellectual functioning, as well as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). His IQ is only 69. During his trial, he said that he didn’t know what the contents of the bundle he was carrying had been, and that he’d been threatened to transport it. The judge didn’t believe him, pinging him for inconsistent statements and ultimately deciding that the statements he made during police interrogation — during which he would have had no access to legal counsel to advise him of his rights or look out for him — were the most credible. There are valid, important questions about how much his intellectual disability affected his decision-making, and his capacity to give clear, coherent statements.

They say that justice must be tempered with mercy. But the death penalty regime neither delivers justice, nor does it show mercy. Nagaenthran — a man with borderline IQ who was arrested with 42.72g of heroin when he was only 21, and who has already spent over a decade on death row — is the proof. What his family is going through now shows us, clear as day, how chillingly inhumane capital punishment is; an entire system of administration bent towards the goal of ending a life.