I do not know if I will be around if this book launch is happening. I hope I will. But if I'm not, my absence will never diminish the reason and purpose of why we have all gathered here. If anything, it affirms our belief in solidarity and the power of collective voices to bring about the changes our society needs.

This is how Pannir Selvam Pranthaman begins his message to those of us who attended his book launch at Gerakbudaya, in Petaling Jaya, on Saturday. Because he's still trapped on death row in Changi Prison, it's delivered on his behalf by Aaron, his nephew.

A book launch is supposed to be a triumph, a celebration of a writer's blood, sweat, and tears finally culminating in a tangible volume. This is even more the case for Pannir, because Death Row Literature: A Collection of Poems is no ordinary book. I'm not suggesting that other poets don't work hard. But most poets I know don't have to deal with the challenges Pannir and his family had to overcome to make this volume a reality.

Instead of a computer and word processing software, all Pannir had to write his poetry with were sheets of scrap paper and the skinny, flimsy plastic cylinder of a ballpoint pen refill. People on death row aren't allowed actual pens; apparently the prison is concerned that the body of a pen could be used as a weapon. So the refills are all they get, and they write sitting on the concrete floor of their cells, because there aren't any desks, either. It makes it even more shocking that so many of the prisoners, including Pannir, have such good penmanship.

Pannir's poems had to be passed, bit by bit over time, to his family during their weekly visits. They were written in letters, written on recycled paper, recited to his sister, passing from his memory to hers. His sisters, Sangkari and Angelia, then had to compile the poems, typing them out to put together a manuscript. Edits were done painstakingly, Pannir making revisions between visits. Completely new to the world of literary publishing, Angelia had to learn fast—securing a publisher, pulling together a budget, finding partners and allies to help cover costs. (Full disclosure: the Transformative Justice Collective supported the publication of this book, along with the Anti-Death Penalty Asia Network, and the NeoKELELims.) Death Row Literature is the result of years of collective effort from both within and without the walls of Changi Prison.

That this poetry collection exists—neatly bound with a pensive, wistful cover—is testament to the determination of a family that refuses to be rendered helpless by incarceration and the capital punishment regime. As Too Xing Ji, Pannir's lawyer, said during his speech, Pannir, who'd received his first execution notice in 2019, has already lived six years longer than the Singapore state intended for him to. He hasn't wasted a single moment. He started reading, first in Malay, then in English. He's now reading The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoevsky's chunkiest work. He's written letters, poems, songs. At his urging, his family have set up Sebaran Kasih, a Malaysian NGO that works with underprivileged communities. He's helped other death row prisoners with their legal applications, encouraging them to fight for themselves even if the world seems to have given up on them—so much so that, according to Pannir's family, the prison now keeps him separate from the other prisoners. He jokes that this is a sign of his power. I don't think it's a joke; I think he's right. And his family, especially his sisters, have matched his power with theirs every step of the way.

Pannir refuses to be defined and dismissed as a Prisoner Awaiting Capital Punishment, as the government calls people on death row. So he's become a poet, a writer, and an activist. The ruling People's Action Party claims that Pannir, and all the other guys on death row, are "drug traffickers" and "proxy murderers" and "scourge of the earth". With every word that he writes, Pannir defiantly shows them—shows us all—that he has grown, he has changed, and he is more. This is what he can do from death row; imagine what more he can do, if allowed to live.

This is what an achievement like Death Row Literature reminds us of. The launch should have been an euphoric celebration of Pannir's victory over a system that's done nothing but try to keep him down and kill him. But as the event programme rolled into a panel discussion on literature and the death penalty—delving into the importance of poetry and writing to encourage empathy and make people consider difficult subject matter—I was suddenly gripped by a nauseating terror.

Pannir is next. Pannir is next.

Singapore carries out hangings in the order in which death sentences have been passed, unless there is some "relevant legal proceeding" that takes a prisoner out of the 'queue'. Last Thursday, Datchinamurthy Kataiah, sentenced to death in April 2015, was killed. Pannir, sentenced to death in May 2017, is now the longest-serving death row prisoner in Changi Prison. That means he's at the front of the line, and a fresh execution notice—his third—could arrive at any time.

Every molecule, every atom, in my body refuses to accept this. Pannir has done everything to prove that he's worthy of redemption—actually, already redeemed—and the state has so far not given a single shit. It's insane to me that our government's position on drug mules is that they must be put to death because they're "proxy murderers" undeserving of mitigation and unworthy of second chances, while our position on politicians leading a state that's committing actual fucking genocide is that "equally bad or worse things are happening around the world, and our approach has to be consistent to all of them", so we won't even entertain the idea of cutting bilateral ties. I don't think it can be any clearer that this isn't about justice or a responding in a way that's proportionate to the harm done. This is about power and privilege and elite interests. People like Pannir and Datch, who come from working class backgrounds and have limited social and political capital, don't have anything Singapore can profit from, so the state treats them as disposable and won't bat an eyelid before killing them in cold blood. But someone like Netanyahu could stain his hands with the blood of thousands of Palestinian children and we'll still do business.

This is the world we live in, and if it doesn't make you fucking livid then you're not paying enough attention. If it doesn't make you want to do something about it, then you're far too comfortable in your bubble.

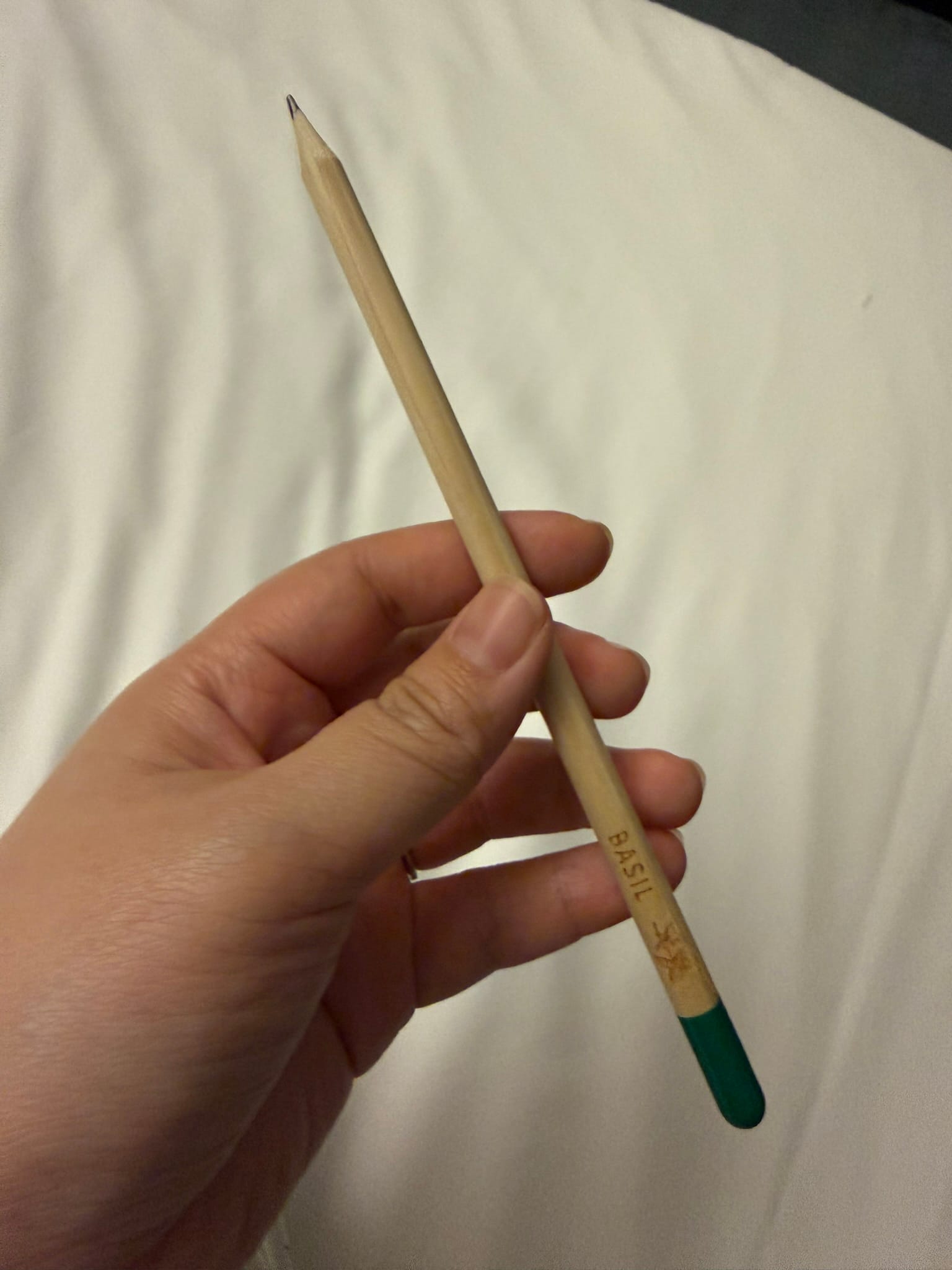

At the launch, we were each given a plantable pencil. Angelia said that Pannir had wanted plantable bookmarks that could be given out with every copy of Death Row Literature sold, but when she crunched the numbers she realised it wasn't feasible to customise them. So she got these pencils instead. Pannir's idea still works with them: no matter what happens to him, the seeds within these pencils can still be planted and grow. No matter what Singapore does to him, he will make his mark. He has already made his mark. People will read his words and think of him, not just as a prisoner, but as a poet who writes about mercy, about faith, about society, about love.

Even if they take everything else, they can never take this away from him.

Thank you for reading this special issue of the newsletter, as well as the previous issue about the execution of Datch.

Datch has been laid to rest, but Pannir is still alive. He has done so much from death row; we, at liberty outside the solid walls of Changi Prison, have no excuse. He's put his faith in us; he's counting on us now.

I'll see you at Hong Lim Park tonight, at 7pm, standing against the death penalty regime and the state killing in our names.

If you'd like to buy a copy of Death Row Literature from TJC, please fill in this form, and we'll post a copy to you once payment has cleared.