The following is a guest post from the team behind the Labour Day rally on Monday.

For most Singaporeans, the Labour Day long weekend might be a good time for a quick weekend getaway, or to trawl through shopping malls staffed by the workers the holiday ostensibly celebrates. That’s how depoliticised Labour Day has become.

This year, local workers’ rights group Workers Make Possible are holding a Labour Day rally at Hong Lim Park under the banner of Manifestival, a series of events held by civil society and social justice groups. Last year, the group raised various issues around working conditions in Singapore, such as the right-to-sit among retail workers, after workers at local retailer Watsons complained of fatigue and chronic pain as a result of their employer’s policies.

Why is Labour Day as depoliticised as it is today?

Even during Singapore’s colonial days, Labour Day was a day of mass political activity among workers. In the 1940s, galvanised by the left-wing, anti-colonial movements in India and China, workers used Labour Day to protest imperialist wars happening abroad and exploitation by employers. Workers participated in a day’s strike and walkouts, attended workers meetings and joined public demonstrations which sometimes clashed with police.

By the 1950s, the trade unions were a major force in Singapore’s anti-colonial movement. In its early years, a large number of PAP members were trade unionists and leaned on the labour movement to gain mass support. A 1955 joint May Day resolution by the PAP and trade unions called for, among other things, a forty-hour work week, unemployment benefits, and a “decent minimum living wage” for all workers.

Once in power, however, the ruling party sought to suppress the movement it came from. They undermined organised labour by giving themselves the power to register and deregister unions. After the schism in the PAP that led left-wing members to leave and form Barisan Socialis, the PAP reorganised unions into the National Trade Union Congress (NTUC), while banning its Barisan-led counterpart, the Singapore Association of Trade Unions (SATU).

With the more radical unions as well as political opposition out of the way, the PAP put the labour movement on the path of “modernisation”, or the pro-employer model of guaranteeing low wages and no strikes that we know as tripartism today. The government justified the need for labour’s “cooperation” with employers as a matter of national interest.

If this sounds familiar, this is the ‘pragmatic’ logic that extends to almost every facet of Singapore governance today. According to the oft-trotted theory by sociologist Chua Beng Huat, citizens are happy to “trade-off” their civil liberties in exchange for economic growth, as the nation’s prosperity would mean better lives for themselves.

Of course, that promise may have never been true for all Singapore residents. While the Singapore government has refused to set an official poverty line, studies have found that around over one in ten Singapore residents live in absolute poverty. The Minimum Income Standard project by LKYSPP and NTU estimated that around 30% Singapore households cannot afford a basic standard of living. And this isn’t even taking into account more than a million migrant workers in the country.

Why Labour Day now?

The wide gulf between those who do and do not share in the nation’s prosperity exposes a system that claims to benefit the interest of all but seems to work only for the few.

In consultation with various civil society and advocacy groups, the organisers of the Labour Day event have come up with 15 demands:

- Stop the 2% GST Hike and introduce a 2% wealth tax on the richest 1% in Singapore.

- Implement a minimum wage for all workers that reflects decent living standards.

- Ensure all workers have enough rest (including the right-to-sit, and a strict cut-off at 20-hour shifts for healthcare workers).

- Provide all workers the right and the financial security to look for suitable work.

- Introduce workplace fairness laws that protect all workers from all forms of discrimination and abuse, and abolish current laws that enable abuse and bondage of workers.

- Give workers direct power to make decisions about occupational health and safety matters.

- Allow all workers the right to unionise, and allow labour and trade unions to function independently and freely, so as to strengthen the effectiveness of labour laws and protections.

- Extend overtime pay to all workers earning $4,500 a month or less.

- Introduce education on local labour laws and international labour standards into upper secondary school civic education or social studies syllabus.

- Expand the Silver Support Scheme to ensure that all seniors aged 65 and above will have at least $1,500 per month in retirement income.

- Make essential foods like milk powder, rice and oil affordable for all through price controls and other measures.

- Make quality healthcare affordable and accessible for all.

- Care for the vulnerable and bring stability to families by making COMCARE payments faster, larger and for longer periods.

- Make sure that those who need welfare and social support schemes don’t have to jump through hoops or endure humiliation. No one should be denied access to necessary welfare on the basis of nationality, employment status, family size, the income of relatives, or other factors.

- Ensure that everyone has access to decent, safe and affordable housing.

Here’s the context behind some of these demands:

Demand 10: Expand the Silver Support Scheme to ensure that all seniors aged 65 and above will have at least $1,500 per month in retirement income.

The Central Provident Fund (CPF) was a pension scheme that was passed by the pro-British Progressive Party before the PAP came into power. In fact, one of the PAP’s 1955 May Day resolutions argued against mandatory CPF, as the “bitter struggle for existence of the workers [...] will become even more bitter for them if their low wages are further reduced by a compulsory contribution of five percent […]”. The same resolution asked that the government first “remove the present insecurity and hardships of the workers before pretending to care for their future insecurity.”

The same criticism can be levelled at the current CPF scheme today; commentators such as Chua Beng Huat have pointed out its failure to provide retirement adequacy for the poor. While richer, middle-class households have greater ability to ‘use’ the range of schemes under CPF — from insurance to assets and savings — to enhance their wealth, those with lower life-time incomes end up unable to meet the Basic Retirement Sum, and can only request monthly cash handouts that are much lower than that of those who meet the retirement sum. In conjunction with the lack of unemployment benefits in Singapore, this effectively forces older workers back into the labour market, typically to take up low wage work.

CPF has since expanded to be more than a retirement scheme, with Singaporeans tapping on it to pay for higher education and public housing. This means that the sky-rocketing prices of public housing is not just an issue of housing affordability, but a threat to retirement adequacy, as the Workers’ Party (WP) has pointed out.

Demand 15: Ensure that everyone has access to decent, safe and affordable housing.

With skyrocketing housing prices and rents, there have been growing calls to bring HDB back from the ‘HDB as an asset’ model that was first advanced in the 1990s.

The current economic model of public housing is a sticky issue. How the ‘fair market value’ of and subsidies for HDBs are calculated has been extremely contentious — commentators like the former GIC chief economist Yeoh Lam Keong have even been POFMA-ed for his remarks.

In short, HDB currently has to foot the ‘cost’ of acquiring the land that flats are built on, which the government values at what they call ‘fair market value’. Considering that the majority of government-owned land was forcefully seized in previous decades from kampung dwellers, farmers, indigenous peoples and others via the Land Acquisition Act, this land was historically acquired for rock-bottom prices.

Opposition party politicians such as Progress Singapore Party (PSP) NCMP Leong Mun Wai proposed in Parliament that HDB prices be delinked from land costs. However, his proposal was immediately shut down and has been characterised by the ruling party as an irresponsible “raiding” of Singapore’s reserves.

Changing the current valuation of land would reduce Singapore’s reserves, where state land resides. However, the question remains: should state land be made available to build public housing at a lower cost or even no cost? Who gets to decide how public assets are deployed, and does the current housing model meet the needs of the public?

Demand 13: Care for the vulnerable and bring stability to families by making COMCARE payments faster, larger and for longer periods.

Demand 14: Make sure that those who need welfare and social support schemes don’t have to jump through hoops or endure humiliation. No one should be denied access to necessary welfare on the basis of nationality, employment status, family size, the income of relatives, or other factors.

The government still refuses to set an official poverty line. However, the Minimum Income Standards project in 2021 estimates that a household of two parents and two children requires a monthly income of at least SS$6,426 to meet a basic standard of living.

Proponents of the poverty line, such as Jamus Lim, cite that it would improve the application process for government aid, which many families have found is often a stressful and even humiliating process.

The people, united

The PAP gazetted Labour Day as a public holiday in 1960, while at the same time stripping unions of their autonomy and decimating political movements through mass arrests and detentions. What has resulted is an extremely depoliticised citizenry that’s often dismissive of people’s ability to come together to create solutions.

When people come together to make their voices heard, alternatives to the government’s proposals are often charged with being populist. Suggestions such as alternatives to raising the GST or changing the HDB’s economic model are depicted as economically unsound or cheap tricks to earn political points at the expense of Singapore’s future (hence, the rhetoric of “raiding the reserves”).

It’s true that concerns around economic and labour issues can often devolve into racist or xenophobic attitudes towards “foreign talent”. However, it is unproductive to reduce people’ real grievances about the material conditions of their lives to simply xenophobia. Unfortunately, when opposition parties give credence to anti-foreigner sentiment, they not only cause harm to communities, they give the ruling party the perceived “moral high ground” against dissenting voices, which are painted as an irrational mob.

In the global marketplace, labour is pitted against labour for access to capital, for jobs and economic opportunities. Meanwhile, our economy is structured around a highly exploited labour force, from the foreign domestic workers who clean people’s houses and raise their children, to migrant workers who are transported at the back of lorries, locked inside their dormitories in prison-like conditions during the pandemic, and even asked not to appear in public areas during Hari Raya.

The migrant worker has limited rights compared to citizens and PRs, and are hence more easily exploited. Despite the huge amount of labour migrant workers perform, employers or the government don’t owe them any rights or benefits, such as basic standard of living or healthcare for long-term medical conditions caused by their work.

Yet, there are many Singaporean citizens or Permanent Residents who can relate to similar labour issues, in kind if not in degree. Many of us feel unhappy with a system that cannot keep running without us, but doesn’t necessarily work for us.

From an understaffed healthcare system which keeps the wages of its workers low, to the skyrocketing price of housing, there needs to be a recognition that the current system based on maximising profits at the expense of our own is not sustainable and hurts all of us eventually.

One of the speakers at the Labour Day rally this year is Mr Chua, a former SBS Transit bus driver who led the case of 13 bus drivers against their employer over a dispute about paid overtime and working hours. The majority of the drivers in the case were Malaysian, but Mr Chua, who led the team, is a Singaporean. When I spoke to him, he shared his view that foreign workers are “easily bullied” by their employers due to their lack of citizenship, while it is harder to ignore the concerns of citizens as they can vote. (Sadly, after they lost the case, all the Malaysian bus drivers involved in the case lost their jobs and had to return to Malaysia.)

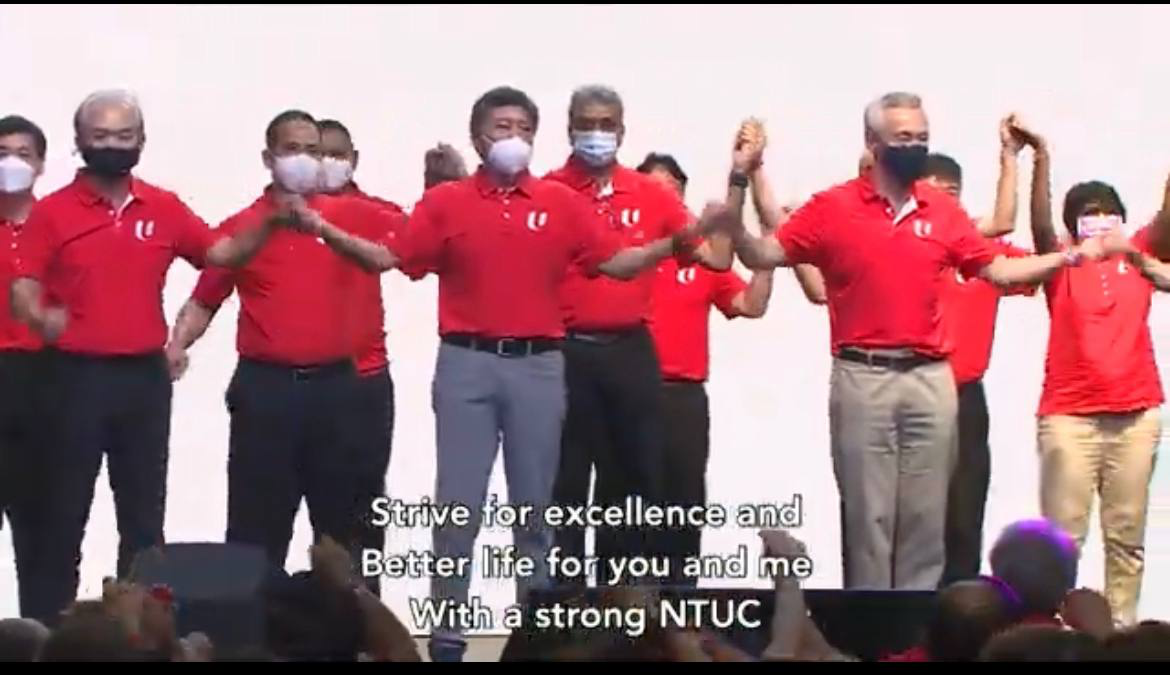

There is only one ‘political’ event on Labour Day each year, and that is the annual May Day Rally held by the NTUC (think National Day Rally but with a focus on labour, where the politicians make speeches extolling the triumphs of the tripartite system). In a video from NTUC’s May Day rally last year, NTUC and PAP leaders are seen gathering on-stage for an awkward rendition of the union classic ‘Solidarity Forever’, but with altered lyrics. Somehow the song’s original lyrics about the exploitation of the working class did not make the cut.

This closed-door NTUC event is certainly not for the everyday Singaporean, even though each and every one of us are workers. Compare this to the joint May Day resolution the PAP co-wrote in 1955, which begins with the line, “To all the workers of this country, of Asia and of the whole world, and to all those who throughout the world are fighting for freedom, democracy and human rights…”

The greatest counter to how this country works right now, where decision-making is conducted by the minority behind closed doors, is for people across Singapore who show up in solidarity with one another to demand and co-create a better Singapore. The greatest threat to the status quo is not something that is populist, but rather something that is popular and oriented towards justice.

If you care about a Singapore that works for all rather than benefit the few, make your voice heard on 1 May, 3–7pm at Hong Lim Park this upcoming week. Do this not just for your fellow Singaporeans and PRs, but also for those who aren't even allowed to enter Hong Lim Park.