This is a out-of-schedule special issue of #wethecitizens to give everyone a rundown of the snappily titled Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Bill that was tabled in Parliament on Monday evening.

What’s the backstory here?

Anti-fake news legislation has been on the cards for Singapore for some time. Back in 2017, Law and Home Affairs Minister K Shanmugam had said that it was a “no brainer” to have laws to deal with fake news. Then in 2018 we had the Select Committee on Deliberate Online Falsehoods, who submitted a report to the government in September 2018. Since then, there has been concern among some quarters (the civil society quarter, basically) that new legislation is going to be fairly draconian and a further blow to freedom of expression in the city-state.

Well, we finally got to see the Bill today. And…

So, what’s the problem with the Bill?

In keeping with what is now a grand ol’ Singapore tradition, the Bill is really broad, granting sweeping powers to the government with limited checks and balances. It has the effect of allowing the government to be the arbiter of truth, if they want to.

Under this Bill, a Minister—any Minister—can issue directives to publish corrections, remove posts/articles, or block access to content. It could be this guy:

Or this guy:

Or this guy:

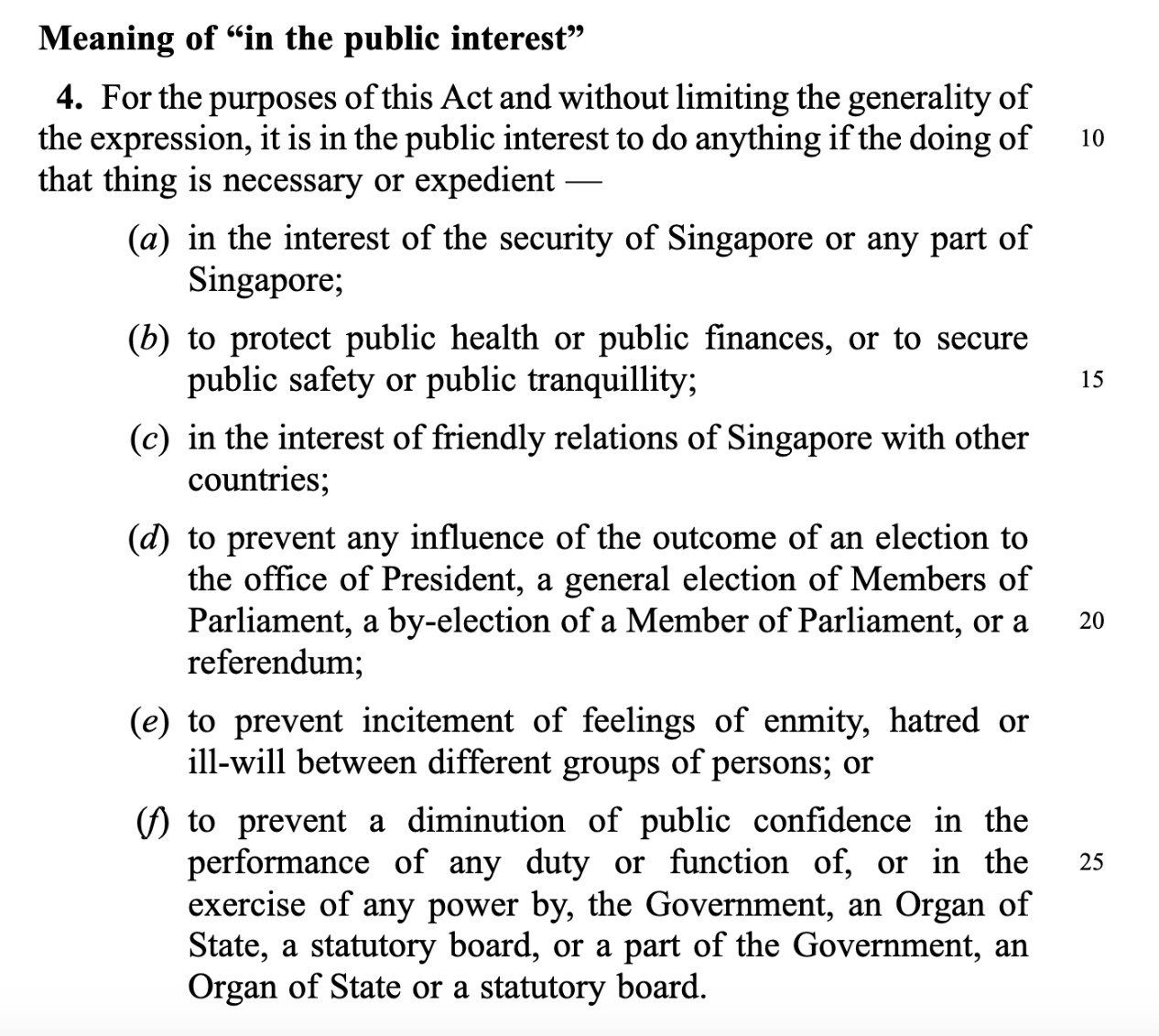

So any Minister can issue these orders, as long as the statement is false, and as long as the Minister thinks that it’s in the public interest to issue the direction. But what’s “in the public interest”?

That covers all sorts of things. And what’s false, you ask? Well, the Bill says “a statement is false if it is false or misleading, whether wholly or in part, and whether on its own or in the context in which it appears.”

At this point, I’d like to remind you that the PAP labelled Human Rights Watch’s report on freedom of expression in Singapore a “deliberate falsehood”. And during the Select Committee open hearing Edwin Tong claimed that my article was misleading because I had referred to “a sit-down demonstration for a cause”, rather than “a sit‑down demonstration for a cause attracts a large group of sympathisers who voluntarily join the sit‑in. For over a week, the group grows and the demonstrators start to occupy the publicly accessible paths and other open spaces in the central business district. Their presence starts to impede the flow of vehicular and pedestrian traffic and interfere with normal trade or business activities in the area.” So that’s the context in which we have to ponder the PAP government’s definition of “false or misleading”.

(If you’re still not convinced, I’d like to further remind you that this is also a government that passed laws that declare that a single person could constitute an “illegal assembly” or “illegal procession”.)

Okay, so the Minister has issued a direction to publish a correction or take down an article. What now? Well, you could appeal to that Minister to change his mind; if he doesn’t, you could apply to the High Court—if you have the time and money—for them to overturn the direction. But the High Court can only overturn the decision in limited circumstances. Who knows how long that’ll take? In any case, you have to publish the correction or take down the content in the meantime—you’ll only get it reinstated if you win in court.

If you don’t comply with publishing a correction or removing content, you could be liable to “a fine not exceeding $20,000 or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 12 months or to both” if you’re an individual. If you’re not, you could get “a fine not exceeding $500,000”. If the Minister demands that an internet service provider block access to content and they don’t, they’re liable to “a fine not exceeding $20,000 for each day during any part of which that order is not fully complied with, up to a total of $500,000”.

There are similar powers over “internet intermediaries” (read: Facebook, Twitter, Google, etc.) too, although the fines can be much higher. And the Minister can also make websites into “declared online locations”, upon which there could be repercussions such as stopping those sites from earning money from advertising.

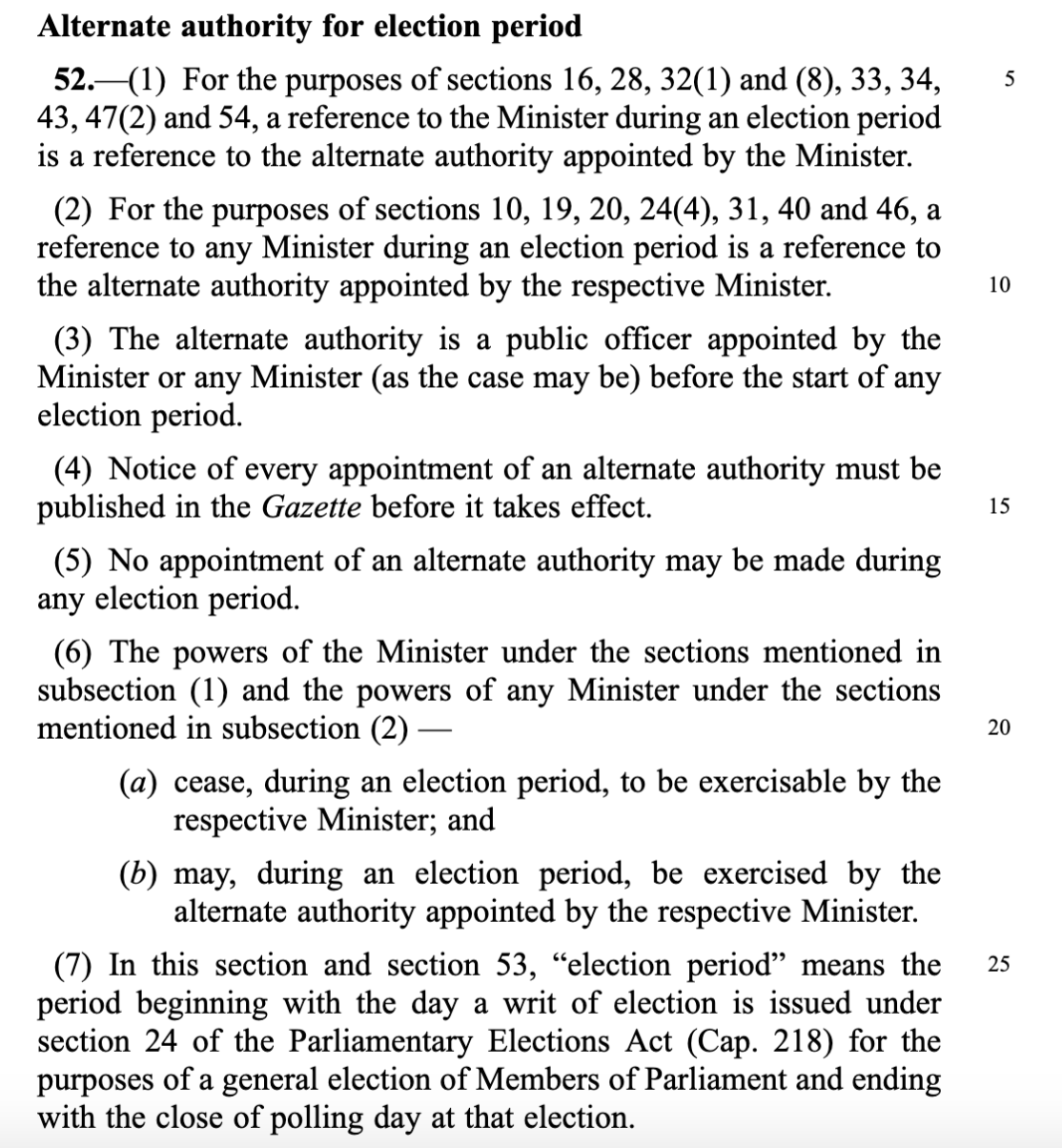

But then you think, “Aha! During the elections, there are no Ministers because Parliament has been dissolved! We’ll be all right then!” And that’s where you’d be wrong.

So before the writ of election is issues, Ministers can appoint public officers to be their “alternate authority”. During the election period, these alternates can then issues orders for corrections, takedowns, or access blocking.

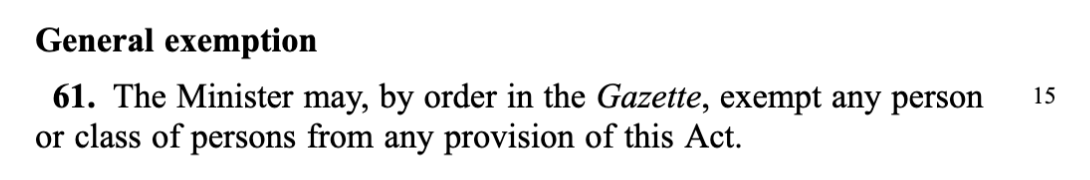

Oh yes, and then there’s this gem stuck right at the end:

This is, of course, not all that’s problematic about the Bill; if I were to go into everything I’d end up just re-typing the entire Bill into this email. I urge you to read the actual Bill yourself.

What are some of the scenarios we might be worried about?

What I’m worried about is that this Bill appears to give the government first dibs on deciding what is or isn’t false, and what the “truth” is. So here are some hypothetical scenarios that I’ve been thinking about:

- Last year, Education Minister Ong Ye Kung stated that there is no discrimination against LGBT people at work or in schools. But LGBT groups have long said otherwise—they point to testimonies of bullying and marginalisation. Under this Bill, could Ong demand that there be “corrections” published on LGBT groups’ websites and articles about LGBT people insisting that there is no discrimination against LGBT people?

- In 1987, the PAP government arrested and detained, without trial, social workers, volunteers and lawyers. They accused the detainees of being involved in a “Marxist Conspiracy” to overthrow the state—a claim that was parroted by the mainstream media at the time. No evidence was produced to back up this allegation, and none of the detainees were tried in an open court. Decades later, the ex-detainees (and many more Singaporeans besides) refer to 1987’s Operation Spectrum as a case of state-sponsored fake news. Are Ministers going to now be able to issue directions asking for Operation Spectrum articles to be removed, or for there to be correction notices insisting that there was a Marxist Conspiracy?

- Because the Bill says that “a statement or material is communicated in Singapore if it is made available to one or more end-users in Singapore on or through the internet”, and makes multiple references to acts committed “in or outside” Singapore, it’s clear the law is intended to have extraterritorial effect. I’m not sure how they’re going to enforce a lot of this with entities that aren’t in Singapore, but my reading is that, under this Bill, any minister could issue a direction requiring, say, the New York Times, to publish corrections or perhaps even remove content that (in their opinion) is against Singapore’s public interest. If NYT doesn’t comply, it’s possible for the Minister to order internet service providers to block access to the NYT in Singapore.

- What avenues do Singaporeans have if it’s the government, or the Ministers themselves, spreading baseless allegations or falsehoods against them?

Isn’t this like the laws in other countries?

One of the ways in which this Bill has been pitched is that it “follows in the footsteps of other countries like France and Germany, which have enacted similar legislation.”

In France, the anti-fake news law allows political parties and candidates to apply to the courts to get false information removed. (This was massively controversial, by the way.) Germany’s NetzDG (also very controversial) applies to social media platforms, not media or messaging services. It requires social media platforms to remove or block illegal content, i.e. content that is already banned by German laws.

In neither of these cases are government ministers given the power to issue takedown orders or correction notices. In the French case, politicians apply to the courts—it’s the courts that rule on whether something gets taken down or not, whereas in Singapore it’s the other way ‘round, where the Minister decides first, and then you can appeal to the court if you are rich enough or brave enough.

Wait, there’s more?!

The Bill in itself is a horror show, but that’s not the end of it. The government is also tabling amendments to the Protection from Harassment Act (POHA), including one that provides recourse to entities rather than just human beings, essentially circumventing the legal victory that The Online Citizen won in the courts over the Ministry of Defence in 2017.

[CORRECTION! Since writing this newsletter I’ve taken a look at the proposed amendments to POHA and am relieved to say that entities as defined in the amendment Bill excludes public agencies. So it does circumvent some of the court ruling (that POHA can only apply to human beings) but not the entirety of it (that government agencies can use it).]

Then there’s talk about regulating offensive speech (read: nowhere near the threshold of hate speech), which included, for some reason, handouts listing “offensive” song lyrics. (If you’d like to indulge in some easy offence, I’ve created a Spotify playlist.)

And this doesn’t include laws to deal with foreign interference, which is yet to come.

Alamak! What can we do about this?

Read the Bill. The establishment narrative is that the Bill is not so bad and that it won’t impact free speech. Don’t just take the government and the mainstream media’s word for it. See for yourself, and decide for yourself. Then talk about it to your friends and family; we need as many people to be educated, informed and aware as possible.