Again, apologies for not having a weekly wrap last Saturday. It's been a stressful week... and then the Foreign Interference (Countermeasures) Bill showed up on Monday! Given that I've been anxious about this law for years now, of course there's gotta be a special issue on it.

After two years of will-they-won’t-they speculation, the PAP government finally introduced the Foreign Interference (Countermeasures) Bill, or FICA, in Parliament on 13 September.

The official narrative is that this law will protect Singapore from foreign meddling in our domestic affairs and governance. We’re told that it’s about safeguarding our political sovereignty. FICA, like the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA), will take on hostile information campaigns, so that Singaporeans can decide on Singaporean issues without the sneaky intervention or sabotage of outsiders.

The reality, though, is that FICA is yet another vaguely worded piece of legislation, designed to give the authorities maximum discretion to cast a wide net over all sorts of activities — including advocacy work by civil society organisations and individual activists. Like POFMA, it hands large amounts of power over to the government, without accompanying checks and balances that will protect people from arbitrariness and potential abuse. The 249-page bill is currently available online, with its Second (and likely Third) Reading scheduled for the next parliamentary sitting.

The reality, though, is that FICA is yet another vaguely worded piece of legislation, designed to give the authorities maximum discretion to cast a wide net over all sorts of activities — including advocacy work by civil society organisations and individual activists.

In a nutshell, FICA targets things like communicating information on behalf of a “foreign principal” without declaring it, hostile information campaigns conducted by or on behalf of foreign actors, and receiving donations or aid from non-citizens. The law directly criminalises some of these acts, or empowers the Minister for Home Affairs or relevant authorities to issue directives that would require recipients to hand over information for investigations into suspected foreign influence, block access to content, carry government notices, or even ban apps from being downloaded in Singapore. Some of the measures in the bill are directed as “politically significant persons”, such as Members of Parliament, political parties, and election candidates. But even if you don’t fall within this category, the relevant authority can designate you as a “politically significant person” as long as your activities are directed “towards a political end in Singapore” and they think it’s in the “public interest” to impose “countermeasures” upon you. These measures can involve banning you from receiving donations from foreigners (or any Singaporean under the age of 21), prohibiting you from accepting voluntary labour from non-citizens, and requiring you to report any direct association or affiliation with a “foreign principal”.

If you thought POFMA was government over-reach, FICA is going to keep you up at night. Everything is extremely broadly defined. For instance, a “foreign principal” is defined as “a foreigner; a foreign government; a foreign government-related individual; a foreign legislature; a foreign political organisation; a foreign public enterprise; or a foreign business”. “Foreigner” is also defined as any individual who isn’t a citizen of Singapore, so, as far as FICA is concerned, Permanent Residents are foreigners too.

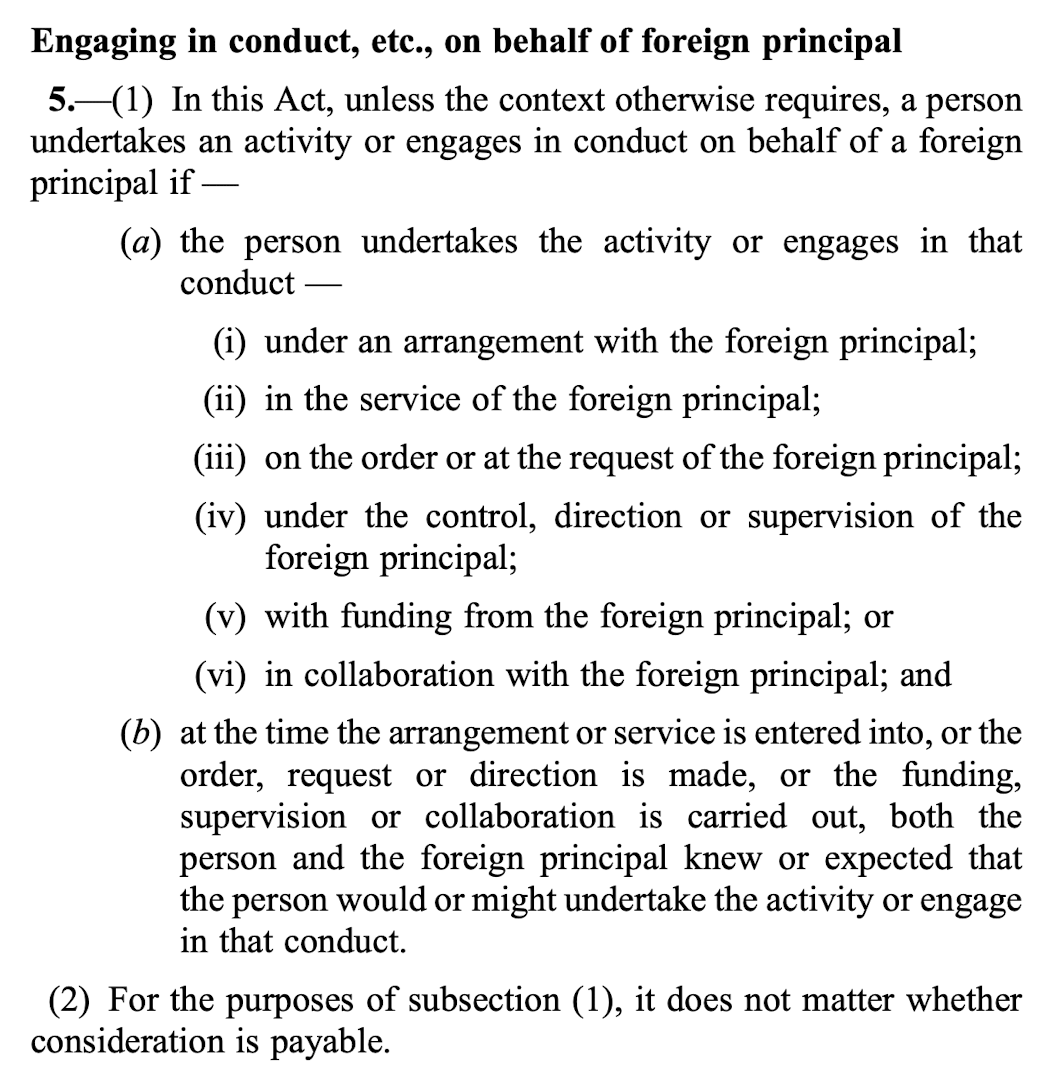

The bill then goes on to define “engaging in conduct on behalf of a foreign principal” in this way:

This wide definition would essentially capture a lot of legitimate activity undertaken by civil society organisations, arts groups, associations, and activists. And we know from experience that the PAP government isn’t shy about throwing this “foreign interference” label around: in May this year, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs took issue with the US embassy for “interference” simply because they co-organised a webinar entitled “The Economic Case for LGBT Equality: Exploring Global Trends with Professor Lee Badgett” with local NGO Oogachaga. New Naratif, a Southeast Asian platform I co-founded in 2017, was also accused of being a vehicle for foreign influence simply because we obtained a grant for independent journalism from Open Society Foundations. (Today, the police issued New Naratif’s managing director, Thum Ping Tjin, a stern warning for the platform supposedly running unauthorised election advertising. The police’s press statement took care to note that New Naratif receives funding from non-Singaporean sources.) Government ministers have also made comments about how The Online Citizen — whose class licence they suspended yesterday — hires non-Singaporean writers. Actually, if you’ve been paying attention to the government’s rhetoric on “foreign interference”, you’ll have noticed that most of their attention seems to be directed not at malicious foreign actors, but at local members of civil society and independent media.

What are we even talking about when we talk about “foreign interference”?

It’s not that malicious foreign meddling doesn’t exist, or that it’s something Singapore doesn’t need to worry about. But we need to be clear and precise about what we’re talking about. Adopting a position that assumes that anything done with funding, support, or collaboration from a foreign source is suspicious, dangerous, or undesirable is not only untenable and damaging to a globalised city like Singapore — wasn’t the PAP just criticising others for being xenophobic? — but also an insult to the agency and capacity of Singaporeans and local movements.

In a world where authoritarian governments can and do learn from one another, where multi-national corporations operate across borders in ways the impact multiple communities with no regard for their nationality, where people, capital, and information flow easily from one place to another, transnational solidarity and activism is important. It shouldn’t come as a surprise, interconnected as we are, that people care about things happening beyond their own borders. People should be able to share knowledge and resources with one another in good faith, even if this doesn’t suit the agenda of the powerful governments and elite networks. In recent years, transnational movements like the #MilkTeaAlliance have sprung up online, as young people in different countries see the parallels and connections present in their struggles and pledge solidarity.

In a world where authoritarian governments can and do learn from one another, transnational solidarity and activism is important.

This is especially important in contexts where there aren’t a lot of resources to go around. Civil society organisations and independent media outlets in the country are consistently underfunded and understaffed. If you work or report on matters that are considered “sensitive” or critical of the government and its policies — which is not the same thing as hurting Singaporeans or the public interest — there aren’t many local avenues that you can turn to for things like funding, training, and other forms of support. Given that the Singapore government tends to dominate the local funding space for the arts and civil society, insisting that people confine themselves to local sources of funding and support can end up being another way to exert control over who can survive and operate, and who will be squeezed out of action.

It also doesn’t automatically follow, like FICA assumes it does, that a Singaporean individual or organisation collaborating with, or accepting help from, a foreigner or foreign entity is working on that foreigner/entity’s behalf. FICA’s logic immediately places the Singaporean in the subordinate position; it’s a mindset that can’t imagine solidarity, equality, and mutual respect (or won’t). The presence of foreign involvement isn’t in and of itself an indication of malicious foreign interference that we need to guard against, nor does it mean that Singaporeans stop being able to make our own decisions.

We do need to be concerned about attempts to manipulate or distort our political processes and democracy, but treating anything with foreign involvement as suspect goes too far, and gives too much leeway for the government to smear its critics and justify taking action against them.

(Always worth reading: this 2020 piece by Dr Ja Ian Chong on dealing with malign foreign interference in Singapore.)

Giving the government more and more unchecked power is a bad idea

FICA builds on POFMA in handing the government more power to not only block content online, but also demand information and impose more surveillance and reporting conditions on individuals and entities. Critics of POFMA already pointed to the problem with executive orders that upend due process, only allowing appeals to court at the end, after compliance has already been required.

FICA goes further. Under this bill, there won’t even be appeals to court. Instead, appeals against directives related to alleged hostile information campaigns will go to a Reviewing Tribunal, the members of whom will be appointed by the President on the advice of the Cabinet. The Minister for Home Affairs also gets to be the one to set the rules and procedures that this Tribunal will follow. If you want to appeal the decision to designate you as a “politically significant person”, you have make your appeal to the Minister for Home Affairs. The decisions made by the Reviewing Tribunal or the Minister are final, and FICA limits the grounds on which you can lodge judicial reviews.

Given the way things are done in Singapore, it’s unlikely like FICA will be used on everyone, just like they haven’t used POFMA on every single piece of misinformation out there. What these laws do is provide the government maximum discretion to pick and choose what and who they want to use such powers on. Past experiences have taught civil society to be worried and wary of such broad laws, but the expansion of unchecked power should be a matter of concern to all citizens. It doesn’t benefit any of us for the space to keep shrinking, and activism to be made ever more precarious, in this way.

If you have some time, do take a look at the Foreign Interference (Countermeasures) Bill yourself!