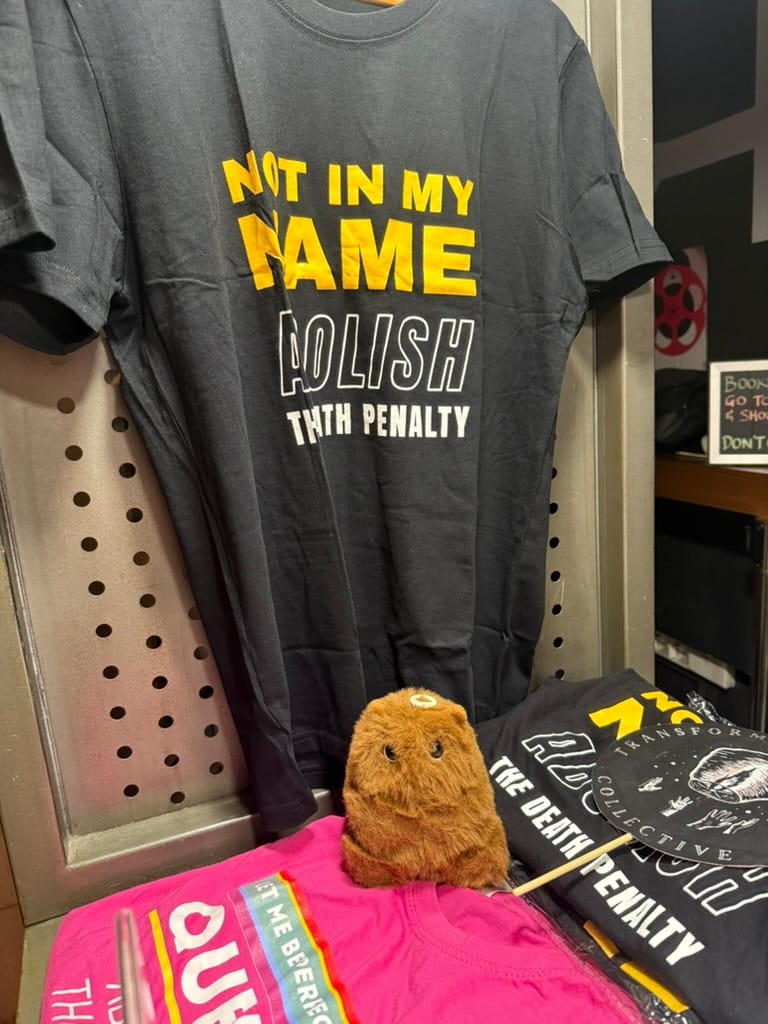

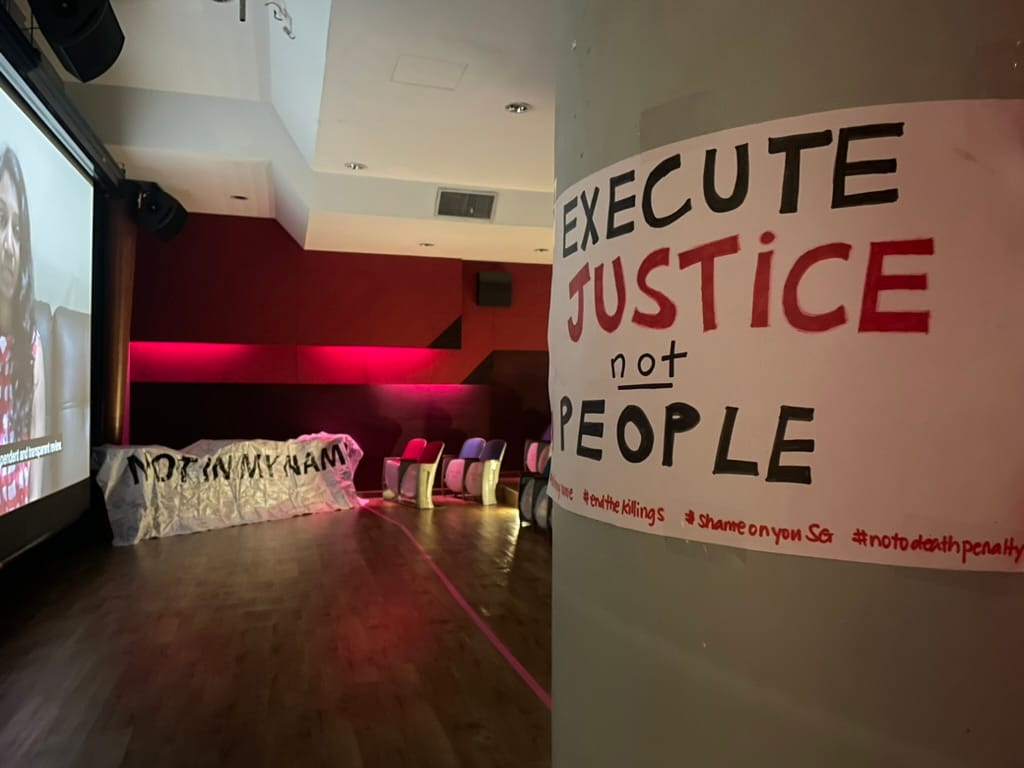

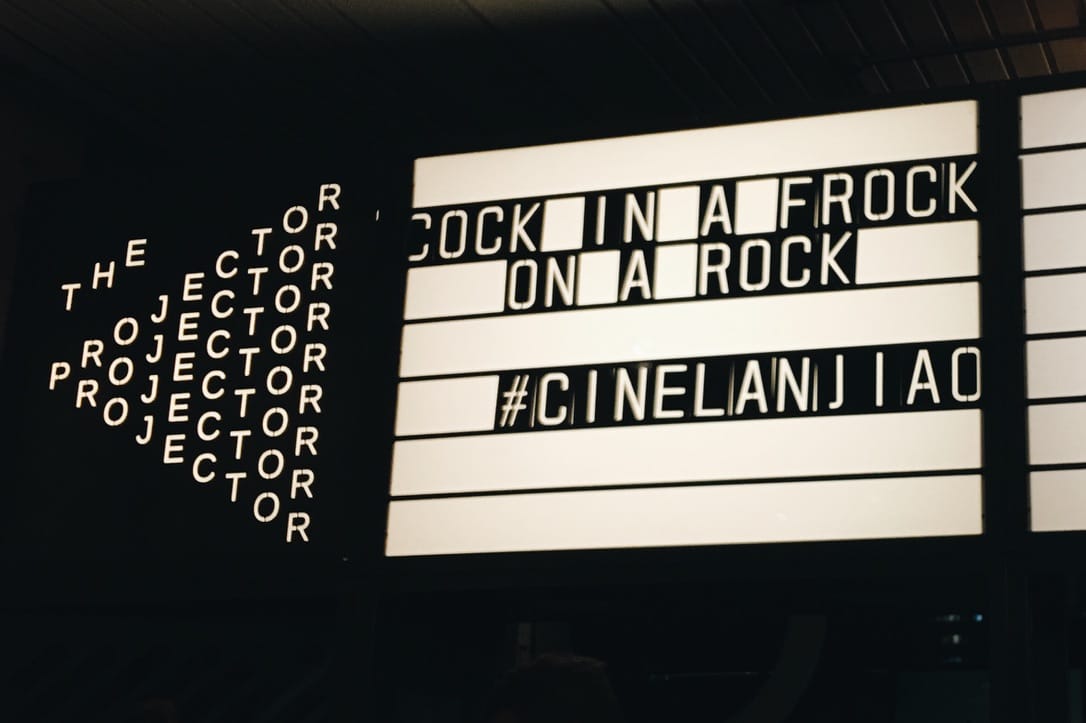

Last month, the Transformative Justice Collective (TJC) ran events for four consecutive days, spanning workshops, speeches, lectures, open mics and community discussions. A week later, NIMBUS, a (broadly defined) independent media network, hosted the third Singapore Independent Media Fair with more than twenty booths and three panels, covering talent development in the creative industries, media coverage of the general election, and reading culture in Singapore. At one point in the afternoon, the crowd at the fair swelled as people came pouring out of a screening of No Other Land, a documentary on the ongoing destruction and oppression of Palestinian communities in the occupied West Bank. All of this happened at The Projector in Golden Mile Tower.

A day after the media fair, at The Projector @ Cineleisure, I moderated a Q&A session with the Japanese journalist and filmmaker Shiori Itō after a screening of Black Box Diaries, the documentary she made about investigating her own sexual assault and how it spurred Japan’s #MeToo movement.

I knew at that point that The Projector was leaving Cineleisure, which I thought was a pity for the ‘hip’ mall of my adolescence, but comforted myself with the knowledge that there would still be their OG home at Golden Mile, where the vibes were superior anyway. I heaved a sigh of relief when I heard that the en bloc sale of Golden Mile Tower had failed; in my mind, that meant The Projector would be guaranteed a home for at least a couple more years. It was devastating to find out yesterday that The Projector has ceased operations because it’s going through voluntary liquidation.

...the realities of the cinema industry have been increasingly unforgiving. Rising operational costs, shifting audience habits, and the global decline in cinema attendance have made sustaining an independent model in Singapore especially challenging. These pressures have been compounded by the broader realities of operating in the arts and culture sector in Singapore, where independent ventures navigate limited resources while contributing to the country’s evolving cultural landscape.

— The Projector’s statement, 19 August 2025

This shock announcement has, understandably, triggered a lot of grief. Ten years isn’t a super long time in the great scheme of things, but it’s long enough for The Projector to have made its mark. So many of us have made friends and memories there. We’ve watched films, launched projects, and participated in discussions on subjects that don’t get much of an airing anywhere else. We’ve danced, laughed, and cried at The Projector. The impact that The Projector has had on people’s lives will never be quantified, only felt and cherished by each and every one of us welcomed into its space. We’ll be feeling this loss for a long time to come.

While moderating the panel on talent development and the struggles of cultural production at the media fair last month, I joked that independent publications and initiatives usually receive the greatest outpouring of love when they’re shutting down; before that, people forget that they need to put their money where their mouth is to keep the work going. There’s some truth to that when it comes to The Projector—a decline in ticket sales is among the reasons they cited—but it’s not the whole story.

Yes, we should try to support independent cinemas, bookstores, cafés, publishers and publications, theatres and community spaces, as much as we can. But we can’t ignore that, for most of us, “as much as we can” is a measure that’s constrained by the realities of life. Cinema tickets, books, food and beverage—the price of everything has gone up. At the risk of sounding old, “back in my day” I went to the cinema with my friends for $7.50 a pop (sometimes $5 on discounted Tuesdays!) and an average paperback would take about $17 out of my weekly allowance. Today, going to the cinema will set you back at least $15 for the ticket and it’s common to pay more than $30 for a book—and it’s not like people’s wages have risen accordingly. I’m happy to spend money to support homegrown enterprises, but there’s a limit to how much I can buy and how much Haram Teh ($18 from The Projector’s Intermission Bar, god I'm going to miss that) I can drink.

We might point to sell-out Taylor Swift, Coldplay or K-pop concerts—where tickets that cost hundreds are gone in a flash—and say accusingly that Singaporeans are just more willing to spend money on these big-name foreign acts than support local initiatives. But while there are things to be said about cultural cringe and the lack of support and investment in the local arts scene, I don’t think it’s fair to judge people for wanting to go see Taylor Swift or paying for Netflix subscriptions. These are all very different experiences, and ideally we should have opportunities to dance to ‘Shake It Off’ and immerse ourselves in an indie movie, but we often can’t because of factors like rising costs, corporate greed, income inequality and diminishing purchasing power.

At the end of the day, Singapore is just a fucking expensive, merciless city, where capital, profit, and wealth accumulation rule the roost. Operating costs like rent are so high that only the most commercial and most money-driven businesses can survive. You either need to have enough capital to go big and maximise economies of scale—like we see with the chain stores that make each mall look like every other mall—or you have to operate at such an intensely optimum level that you can’t really afford to have a slow month or even a slow week. And this at a time when, thanks to the pandemic and economic downturn, many businesses have had (or are still having) slow years.

I’m not saying that even poorly run, failing businesses should be able to stay open forever. But if we want innovation, diversity, vibrancy, and depth in our society and cityscape, then it can’t be so relentless. Not everything is going to be a winner every time. Not every theatre will see a full house, not every café or restaurant will be fully booked. Not everything is about profit maximisation, and that’s what makes them meaningful and valuable. Independent endeavours can’t just keep relying on their ordinary, wage-earning customers spending (or donating) more and more as costs go higher and higher because landlords want more and more or inflation goes up and up. There has to be some breathing room, so that the stakes of generosity (like giving low-resourced groups space at a discount, as The Projector did), experimentation, or even failure aren’t so devastatingly high.

Reeling from the news, people have been brainstorming ways to save this beloved space. Just from conversations among friends and casual browsing on social media, I’ve seen suggestions of crowdfunding campaigns, of buying over The Projector, of converting it into some sort of collectively run social enterprise. A petition is also circulating with an appeal to the government to save The Projector—described as a “cultural infrastructure asset”—with a rescue package of “grants, low-interest loans, or strategic support measures”.

I’m heartbroken by the thought of a Singapore without The Projector, but I don’t think government intervention is the answer. We’re all familiar with what happens when the government steps in and “aligns” a venue or organisation to its “strategic goals”. The Projector was precious precisely because it was independent of the state and the government, which meant it was willing and able to host events and screen films that those in power would rather keep suppressed. (Which other cinema would have screened 1987 Untracing the Conspiracy, with Q&A sessions with the Operation Spectrum detainees?)

If the government (i.e. the country’s biggest landlord) wants to help, it'd be much better off doing something about broader, structural conditions, like the rent-seeking behaviours we’re seeing across the country. The Projector is not the only local business forced to throw in the towel. Singaporeans have been enduring loss after loss—favourite cafés, local bakeries, old eateries, arts venues, familiar spaces that hark back to our childhoods and give us a sense of continuity and home.

This city won’t let us live. That was the first thought that popped into my head when I read The Projector’s statement. For ten years they’ve been a safe place for us, a place we could count on to not back out and leave us in the lurch while other venues get nervous about “sensitive subject matter” and refuse to host or, worse, cancel on us. Last month, when the Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA) sprang unreasonable licensing requirements on TJC just days before TJFest, making it difficult for us to proceed with our original venue, it was The Projector who welcomed us to their space. We could breathe at The Projector. Its closure feels like being dunked underwater once again.

The Projector has been such a key fixture in civil society—the setting of so many beautiful, nourishing, energising experiences—that I now feel bereft and adrift. I don’t know where else we can go for our events and activities. I’m not yet able to fully picture the impact this loss of space will have on civil society as a whole, but today Singapore feels a little colder, a little more hostile.

In time, another space might emerge. I think it will, because even if it doesn’t feel like it at the moment, Singapore has always had some never-say-die dreamers. Who knows, maybe it’ll last longer than ten years next time. I can only live in hope.

Right now, though, it feels like we’ve lost a piece of our collective heart.

Thank you, The Projector, for all you've given us. You'll be so greatly, deeply missed.