Update (6 April 2024)

In a statement issued today, the Ministry of Manpower and the Singapore Police Force denied advising Sharif’s employer to terminate his employment. They’ve also committed to giving him a Special Pass to remain in Singapore until the conclusion of his investigation.

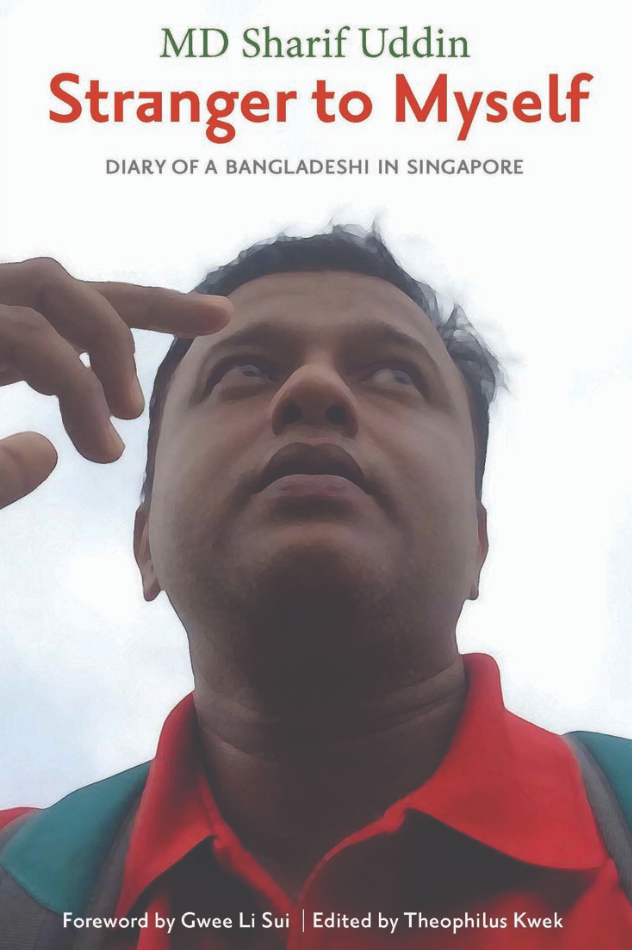

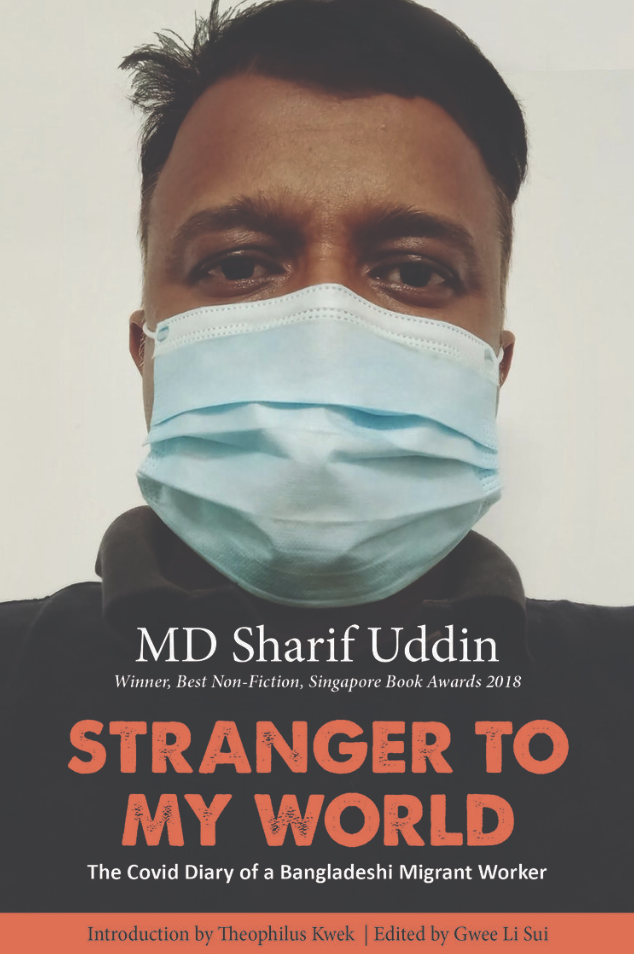

You might already know of Uddin MD Sharif, known to his friends as Sharif bhai. He’s a prominent member of the migrant worker poetry community in Singapore, and has published two books, Stranger to Myself: Diary of a Bangladeshi in Singapore and Stranger to My World: The Covid Diary of a Bangladeshi Migrant Worker. He won Best Non-Fiction Work for the former at the 2018 Singapore Book Awards—the first migrant worker to clinch this prize.

Despite the titles of his books, Sharif is really no stranger to Singapore. He’s been working here for the past 16 years, part of the huge labour force that has literally shaped our city’s landscape. In his last role, he’d been a safety coordinator* on a piling site. He’s also been a leading voice in speaking out about migrant workers’ labour and living conditions and rights from the perspective of a migrant worker—a rare sight in a country where these low-wage workers are systemically disempowered and not allowed to assume leadership positions in the registered NGOs that advocate for their interests. “I want to talk to people. Maybe this book [Stranger to My World] can help them understand what we need, what we want, what goes on in our minds,” he said about his Covid diary. In 2022, Sharif was a co-organiser of the arts exhibition A Journey By Lorry that aimed to draw attention to the dangerous practice of ferrying migrant workers in the backs of lorries not meant for passenger transport. Contributions to the art exhibition were later collated and published in book form. But Sharif is now facing repatriation for a situation that was neither of his making nor within his power to control.

A letter arrived at the end of January this year, delivered to Sharif’s employer. Enclosed in the letter were photocopies of both sides of his work permit alongside joss paper hell notes. The message claimed that Sharif owed money and demanded he repay his debt. It was the first in a series of such harassing letters, sent to both the company office and to Sharif’s employer’s home. The company office also received a threatening phone call.

“Strangely though, Sharif himself wasn’t contacted by the harasser,” the civil society group Workers Make Possible notes in an Instagram post reporting on Sharif’s situation. “None of the mail or calls his office received contained demands about how much money was owed, how it should be paid, and to whom. When Sharif repeatedly tried to call the number his office said they received a call from, it was disconnected.”

Sharif says he’s never borrowed money from any loan sharks. “The first time they received [this letter], the office thought I’d taken a loan. I said I one cent also never take.” His employer told him to settle the matter. “How to settle?” he asked me over the phone. He had no idea where these letters were coming from.

Sharif’s employer reported these letters to the police, and he spoke to the police over the phone more than once in early February. Still the harassment continued. On 11 March, the company decided to sack Sharif.

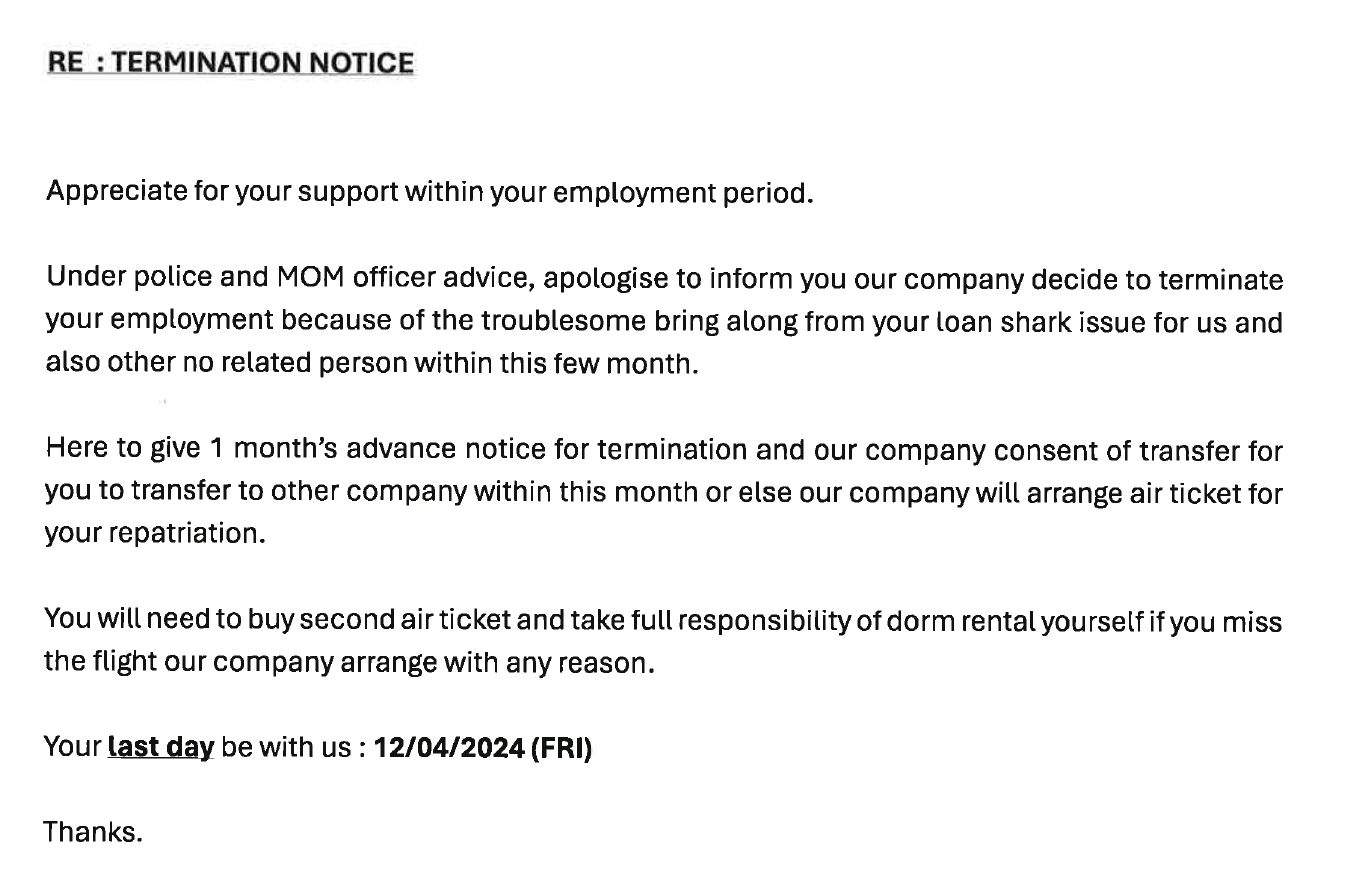

In the termination notice Sharif showed me, the letter says: “Under police and MOM [Ministry of Manpower] officer advice, apologise to inform you our company decide to terminate your employment because of the troublesome bring along from your loan shark issue for us and also other no related person within this few month.” It also expresses the company’s willingness to transfer him to another employer, should he find one within a month. Otherwise, Sharif will be sent back to Bangladesh. The letter states that his official last day is 12 April 2024.

Sharif also showed me the police report he’d lodged the day he received this termination notice. “My company had reported the case to the police on several occasions with the first-time police was informed was on 5/2/2024 after my manager had first received the letter and hell note,” he is recorded as having told the police. “I wish to add that I did not borrow any money from any loan sharks, I did not contact any of the loan sharks and I was not contacted by them at all. I strongly believe someone is impersonating and misusing my work permit to borrow money from the said loan sharks. I had tried to ask for further details from my company regarding the letters and calls received they had received however they did not elaborate on what the contents were. I am now lodging this report as I want to prove my innocence and for the person impersonating to be brought to justice.”

Things looked like they might have taken a turn for the better when Sharif secured a new job about a week later. The new employer applied to MOM for his work permit to be transferred. If everything went smoothly, Sharif would be able to continue working in Singapore.

Then the harassing messages were delivered to the new employer.

Sharif was still befuddled by this when we spoke over the phone on Tuesday night. In search for an explanation for this mess, he’d initially considered the possibility that someone might have been after his job—perhaps they’d hoped to drive a wedge between him and his employer, get him fired and take his spot. But that couldn’t be if the harassment had followed him to the second company. And how did the harasser find out where he was transferring to? Sharif told me that only his first employer, the new employer and MOM knew about this development.

However the harasser found out, their threats have already taken effect—the new company is now unwilling to hire him. Sharif is back to square one: unless he finds a new job by 12 April, he’ll be sent back to Bangladesh.

Shocked. Surprised. These words crop up over and over again during our call. Things had been going well before all this. He told me that his boss had even renewed his work permit at the end of last year, which he took as a sign that they were happy with his performance. He’d had a good relationship with the company and expected to keep working for them. He’s 46 this year and has given so much of his prime to building Singapore. He has a teenage son and a six-month-old baby, and is the sole breadwinner for an extended family. He told me that he’d planned to work a few more years in Singapore and save up a bit more before returning home. Now it feels as if a rug has been pulled out from under his feet. “This all happened so suddenly, I was so surprised.”

Sharif is also taken aback by his employer’s claim that the ministry and police had advised them to terminate his employment. “I’m very shocked, I’ve worked for four years for this company,” he said. “Why did they give me a termination letter without proof [that I had really borrowed from loan sharks and caused these problems]?” He wonders if his bosses would have made a different decision if MOM and the police had given different advice.

“What are they thinking?” Sharif wonders about the authorities. When he made his report in March, the police had written down what he’d said and told him that they’d investigate. But “they one time also never call me, never update me”. He’d expected more follow-up and isn’t sure how the investigation is going at all—he hasn’t been able to speak directly to the officer in charge.

Sharif has since written to MOM and the Singapore Police Force (SPF) detailing his situation and asking questions about the status of the investigation and their position on the harassment he’s experienced. Did they really suggest to his employer that they should sack him and send him back to Bangladesh? He says he’s received a response from the police acknowledging his email, but hasn’t heard anything more substantial thus far.

I’ve also sent questions to MOM and SPF. In an email I sent on 31 March, I asked the following:

- I understand that police reports were made about harassing letters sent to Sharif's employer, and that both MOM and the police advised the employer to terminate Sharif's employment. Can MOM and SPF confirm that they did indeed give such advice to the employer?

- If such advice was indeed given, can MOM and SPF please explain why they would advise employers to take such action in such circumstances? Have there been other such cases where, in response to reports of harassment or other issues faced by a migrant worker and/or his employer, the advice was to terminate the worker's employment?

- What is the current status of the reports filed by Sharif and his now former employer to SPF? Have the police opened an investigation? If not, why not?

- Sharif has also emailed MOM and SPF with questions—what are your responses to his queries?

I asked to hear back by 5pm on 2 April. Apart from automated out-of-office responses from some of the MOM or SPF comms officers I’d emailed my questions to, I haven’t received any response.

Sharif has spent over a third of his life in Singapore—now he feels betrayed by his employer, the ministry and the police. The worker is powerless here, he says. He doesn’t know how his harasser got hold of his work permit—as sensitive to a migrant worker as the NRIC is to a Singaporean—but there are so many circumstances in which workers are expected to show or hand over their permits to all sorts of people, from contractors to security on work sites to administrators and doctors and dorm operators processing security passes. This work permit is what allows a migrant worker to remain in Singapore, but employers can terminate it easily, which is why his company is able to fire (and potentially repatriate) him rather than wait for the outcome of the investigation. On top of that, Sharif has zero control over how the police conducts its investigation, nor does he have any idea how long they might take. Yet he is the one who is on the hook to pay the heaviest price.

Before we end our phone call, I ask Sharif if he has anything else he wants to say. He doesn’t hesitate. “This is totally unfair. This procedure is totally wrong.”

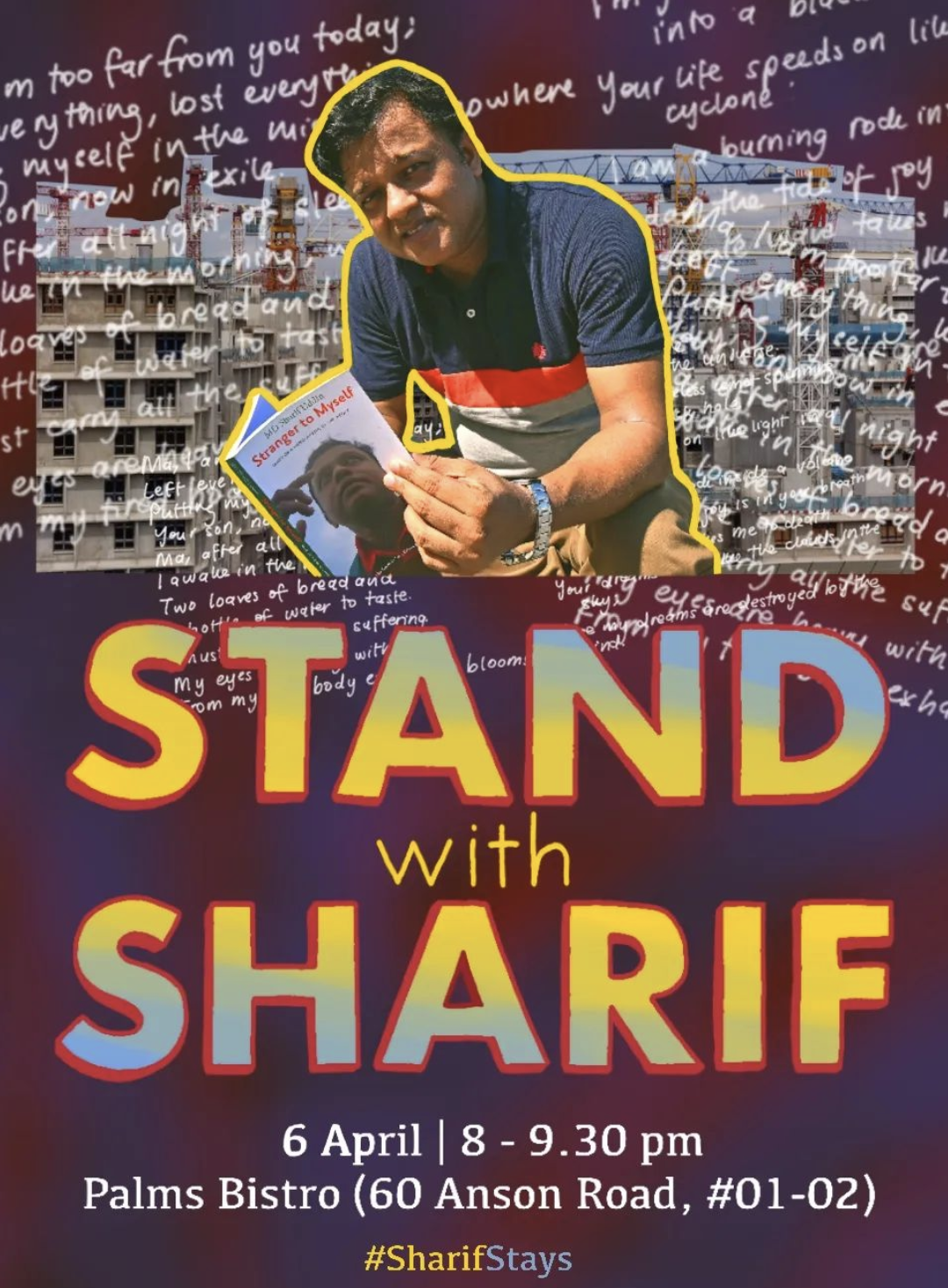

In solidarity with and support of Sharif, Workers Maker Possible and Students for Migrant Rights have organised Stand With Sharif, an event to draw attention to his situation. There will be readings of passages from his books, as well as the sharing of messages of solidarity and a reflection of the state of migrant workers’ rights in Singapore.

The event will be at Palms Bistro (60 Anson Rd, #01-02, Singapore 079914) on 6 April 2024, 8pm–9:30pm.

Workers Made Possible has also launched an online petition that you can sign here.

* A correction!

The original email sent out described Sharif as a "safety supervisor" but the right title is "safety coordinator", so I've changed it.