I’ve edited this piece because, at the time of writing, I missed that 127A of the Prison Regulations had been added in September 2018, while the prison forwarded Syed’s correspondence in May and June of that year. Therefore, at the time of them forwarding the correspondence, there was no clear provision saying that they weren’t allowed to make copies of his letter to his lawyer. That said, the problem with forwarding privileged communication still stands!

While in prison, inmates surrender much of their autonomy and agency, relying on the authorities to manage aspects of their lives, like their ability to work or study. Most particularly, they are reliant on the prison to facilitate their access to and contact with the outside world, be it visits from family and friends or writing letters and making phone calls.

Given this, it’s alarming to discover that, in 2018, the Singapore Prison Service forwarded five letters written by death row inmate Syed Suhail bin Syed Zin to the Attorney-General’s Chambers (AGC). Among these letters was one that Syed had written to his then-defence counsel. At that time, Syed was in the middle of appealing his conviction and death sentence to the Court of Appeal, with the AGC as the prosecution.

Syed had a hearing before the Court of Appeal on 3 May 2018. According to the minute sheet, he’d sought an adjournment of his appeal so that he could include new evidence from his uncle to his case. Directions were given by the court to both the prosecution and defence, with the matter “to be restored for hearing at the first sitting of the Court of Appeal in July 2018, at which time the court will decide whether to proceed with the hearing of the appeal, or to give further directions.”

Following that hearing, the Singapore Prison Service sent the prosecution four letters that Syed had written to his uncle, as well as a letter that he’d written to his defence lawyer. “[The] correspondence came into the AGC’s possession from the SPS on 10 May 2018 and 7 June 2018 for purposes of preparing the Prosecution’s response,” wrote the AGC in a letter to the registrar of the Supreme Court, signed by Deputy Public Prosecutor Francis Ng and dated 18 September 2020.

[The rest of this section was edited to reflect that 127A of the Prison Regulations did not come in until after the prison forwarded Syed’s letters.]

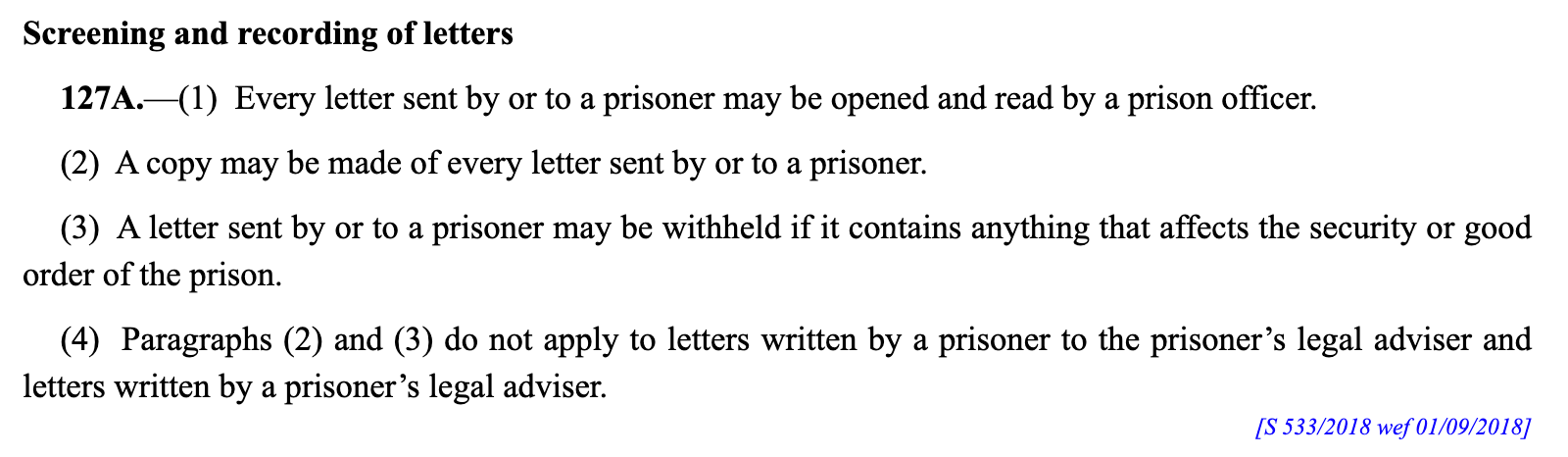

Months after the prison service sent the correspondence to the AGC, the Prison Regulations were amended to state that the prison is not allowed to make copies of correspondence between an inmate and their legal counsel.

(Screencap from the Prison Regulations.)

“Safeguard the rights of prisoners”

This isn’t the only time the Singapore Prison Service has forwarded prisoners’ correspondence or documents to the AGC.

In a written judgment published in August this year, the Court of Appeal noted a complaint made by another death row inmate, Datchinamurthy a/l Kataiah, against the Singapore Prison Service. Datchinamurthy had protested against the prison forwarding copies of documents that his relatives had brought to prison to the Attorney-General’s Chambers — an act that neither the AGC nor the prison denied. Instead, their position was that “the documents were neither confidential nor privileged as they were not exchanged between the appellants and their legal advisors.”

However, the Court of Appeal stated that while the Prison Regulations allow the authorities to open, screen, and make copies of inmates’ documents, these powers were provided to facilitate the “good management and government” of prisons, and do not extend to forwarding these documents to the Attorney-General’s Chambers.

“There is an expectation of confidentiality in a letter or document shared between private parties,” wrote judges Andrew Phang, Judith Prakash, and Woo Bih Li. “These are documents and information that the SPS has access to by virtue of its administrative role under reg 127A to screen and record letters, but there was no legal basis in the form of a positive legal right to forward copies of the same to the AGC.”

“We also highlight that even if the documents were not privileged or confidential in the strictest sense of the word, they were still the prisoners’ personal property,” the Court of Appeal added. “If the AGC had wished to obtain copies of letters belonging to the prisoner that were in the SPS’s possession, the proper procedure would have been to obtain the prisoner’s consent or an order of court.”

Besides Datchinamurthy’s complaint, the Attorney-General’s Chambers raised another example of the prison forwarding inmates’ private correspondence at the hearing of this case. In this instance, the AGC had forwarded the prison a copy of the official minute sheet for a court hearing so that Datchinamurthy and his fellow appellant Gobi a/l Avedian could share these details with their family.

As stated in the Court of Appeal judgment (emphasis mine): “The AGC asked the SPS to notify it when the appellants had sent the minute sheet and, in that context and without a specific request from the AGC for these documents, the SPS proceeded to forward copies of the appellants’ letters to their families to the AGC.” (In this case, the AGC had agreed that copies of such correspondence should be destroyed.)

While, in the case of Datchinamurthy and Gobi, the Court of Appeal accepted that the forwarding of correspondence had been an “oversight” on the part of the AGC when it came to inmates’ privacy, and had not been “an attempt to seek an advantage in the proceedings”, it emphasised the importance of justice not only being done, but being seen to be done.

“As guardian of the public interest, there is… a duty to safeguard the rights of prisoners in the custody of the SPS,” the judges wrote.

Questions

In the light of the Court of Appeal’s guidance in Datchinamurthy and Gobi’s case, the Attorney-General’s Chambers has stated that they will destroy all copies of Syed’s five letters in their possession. They’ve also declared that the deputy public prosecutor now attached to Syed’s case had previously not been “aware of the existence of the correspondence” as he hadn’t been involved in Syed’s appeal, “and that he has not looked at the contents of the correspondence and is not otherwise aware of these contents.”

Still, these revelations raise further questions that should concern anyone who cares about Singapore’s criminal justice system.

Death row inmates and their families previously reported seemingly arbitrary rules imposed by the prison when it comes to communicating with people outside prison. In 2016, the family of Kho Jabing (executed in May that year) said that he had been told that he would not be allowed to write letters out. In a recent community teach-in, Syed’s sister Mila said that her brother had once been told that he would not be allowed to send letters with similar content to more than one person (the prison later relented). After faxing his letters on his behalf, the prison also does not return the letters to Syed.

These experiences highlight the amount of power that the prison authorities have over inmates’ ability to communicate with others. On top of this, it’s now revealed that prisoners’ private correspondence have been forwarded by the prison to other parties without their consent.

In defending their actions in sending on, and receiving, Datchinamurthy’s documents, the AGC and the prison argued that the documents had not been privileged and confidential since they hadn’t been between Datchinamurthy and his legal counsel. Yet, in Syed’s case, one of the letters had been between him and his lawyer. Why, then, did the prison send a copy of the letter to the AGC? And why did the AGC not flag this matter in 2018, especially since Syed’s appeal was still pending before the court?

It’s worth noting that the letter from the AGC to the court flagging that Syed’s letters were in their possession was dated 18 September 2020 — the date on which Syed had originally been scheduled to hang. If Syed had not managed to get pro bono representation, and if his new lawyer M Ravi had not filed applications that led to the High Court giving an interim stay of execution, would Syed have been hanged and this matter never come to light?

Beyond Syed, Datchinamurthy, and Gobi, how many other prisoners, particularly death row inmates, have had their correspondence and documents copied and sent on by the prison? Have there been other instances of correspondence between an inmate and his legal advisor copied and forwarded to the prosecution? If so, what were the contents of those letters, and could there potentially have been prejudice to the inmate? Should there not be an independent inquiry where both the Singapore Prison Service and Attorney-General’s Chambers provide a list of such forwarded correspondence and documents, so that each case can be examined for any potential prejudice or miscarriage of justice? This is especially important when it comes to capital offences, where lives are at stake.

I have sent questions to both the AGC and the Singapore Prison Service, and will update this piece if/when they respond.

The Singapore Anti-Death Penalty Campaign (SADPC) and the Community Action Network (CAN) have released a statement.