It’s a regular day, you're playing phone games during your MRT commute, and suddenly you get a call from a cop, out of the blue. They tell you that there's an issue, related to a months-old Facebook post you don't even remember, that they have to talk to you about, so you need to meet them at the police station. They refuse to give you any more information about what it's all about.

What would you think? What would you do?

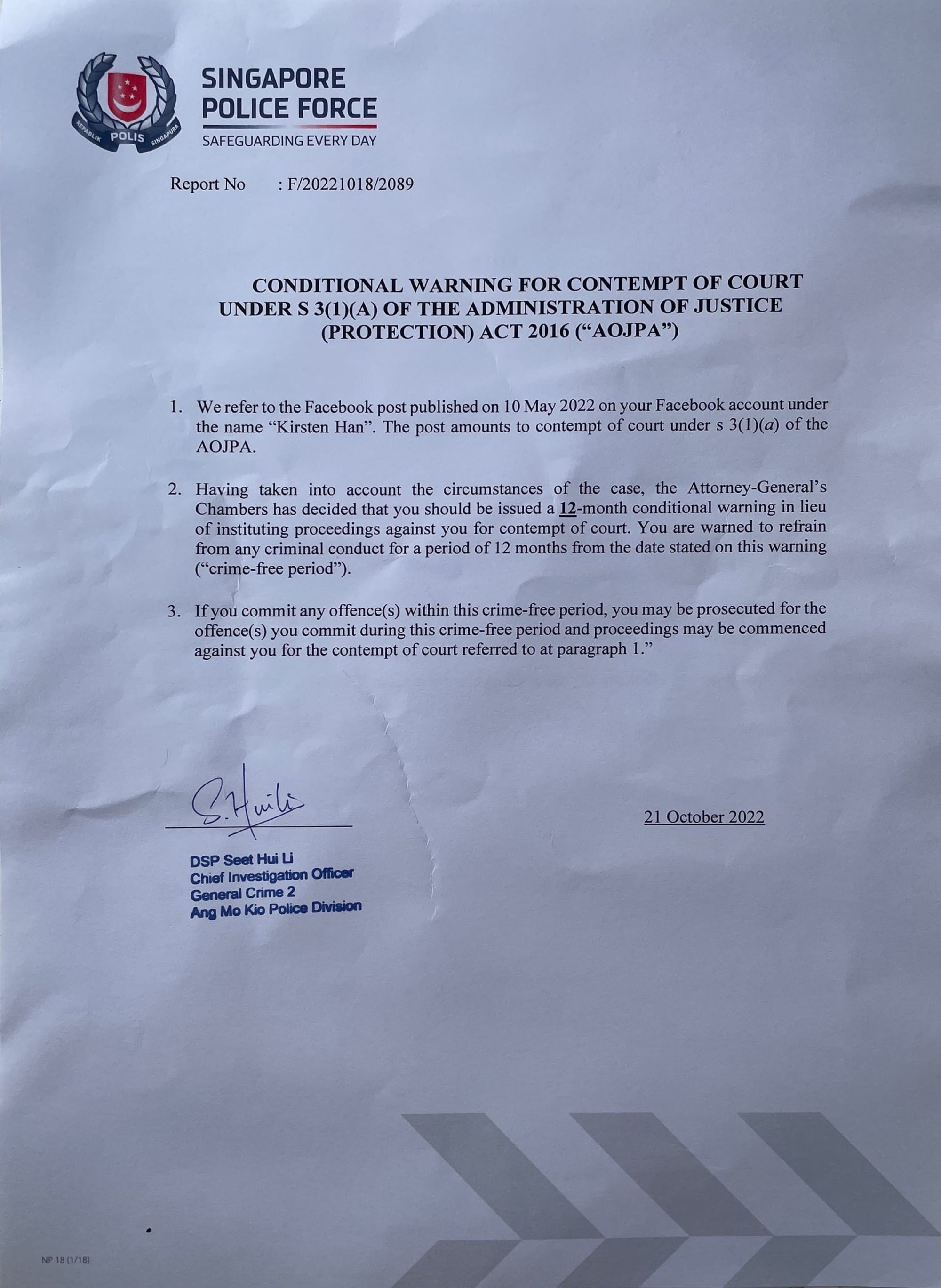

Last November, I sued the state over a conditional warning that the Attorney-General's Chambers (AGC) had told the police to give me. The judgment has been released.

tl;dr I lost.

I attended the hearing with my lawyer last month. It was only in the run-up to this hearing that I discovered that, in civil proceedings where hearings are held in chambers and the applicant has a legal representative, the usual practice in Singapore is that the applicant does not attend. My lawyer had to write to the court to seek permission for me to attend a hearing of my application.

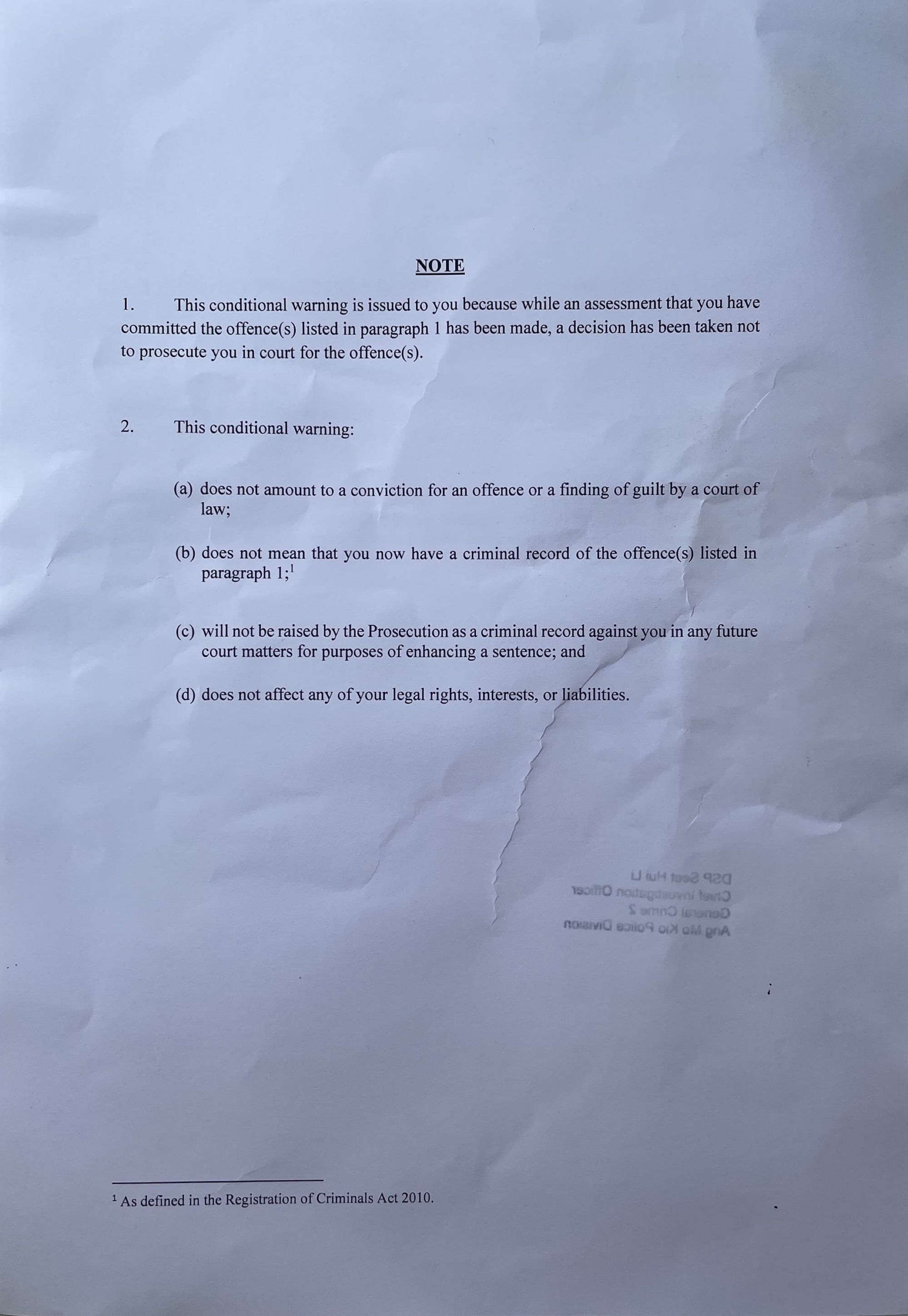

There were a number of prayers in my application, so I'll just zero in on the main points. I asked the court to quash the 12-month conditional warning that I'd been issued. My lawyer argued that conditional warnings do have legal effect, because the whole “stay crime-free for X period of time or we'll charge you for this offence and the new offence” indicates that the prosecution undertakes not to prosecute for the offence that's the subject of the warning as long as the individual complies with their stipulated condition.

We also pointed out that it was problematic that the warning hadn't explained which part of my post was in contempt, and that it wasn't right for the police to act on the AGC's direction without carrying out their own investigation (in the judgment, it’s stated that the AGC told the police to give me a warning but did not authorise the police to conduct an investigation into the alleged contempt).

Another major point was that the police's insistence that I go to the police station was illegal or irrational, because they actually had no power to compel me to go down to the police station, and could have delivered the warning in another way.

In his judgment, Justice Kwek Mean Luck dismissed all the prayers. He found that conditional warnings do not have legal effect — and are therefore not susceptible to judicial review — and that there was no “real controversy” to be resolved in the matter of my attendance at the police station. (Funnily enough, my lawyer was told the day before its release that I would have to pay $65 for a copy of the judgment, but then it was uploaded online for everyone to download? So just ended up getting it off the judiciary website for free like everyone else…)

What really struck me throughout this whole process is how removed the legal process and arguments were from my lived experience. I was surprised by how disorienting it felt.

During the hearing, and now in the judgment, it was emphasised that the police hadn’t actually forced me to go to the police station. It’s true that the police did not have the legal power to compel my attendance at the police station solely for the purposes of collecting a conditional warning. But I don't think it's right to say that I'd gone of my own free will.

Let's go back to the scenario that I'd opened this piece with, and what happened next:

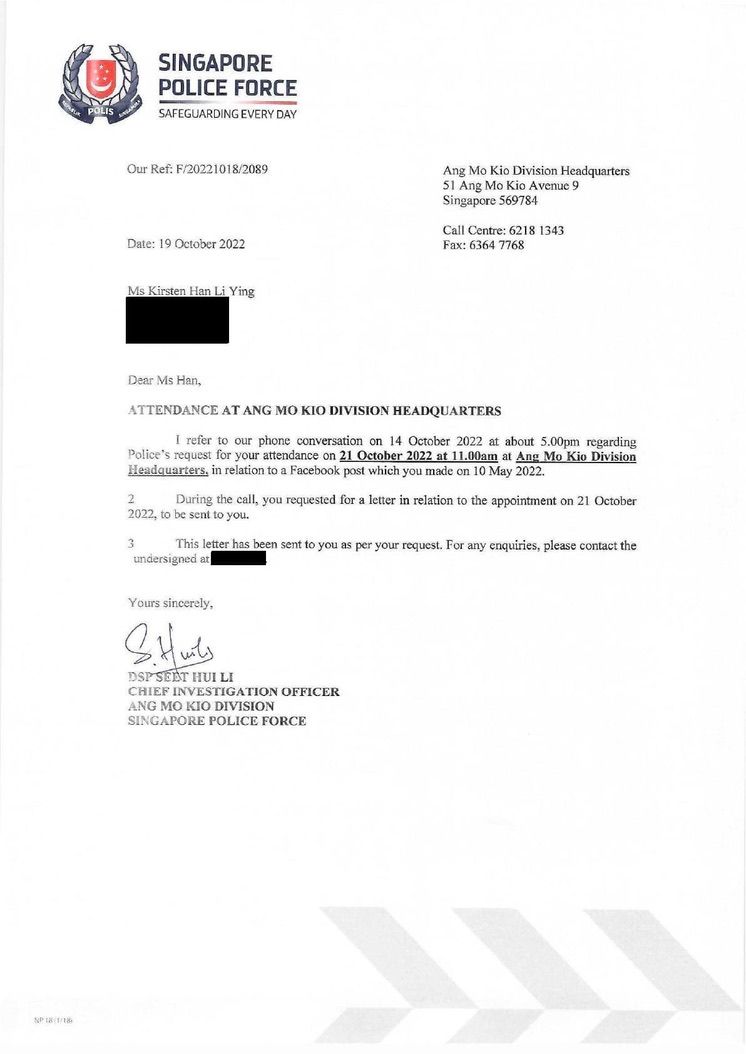

- I receive a call from a police officer out of the blue. She tells me she needs to talk to me about something related to a social media post, but refuses to tell me anything more, even when I ask. She just says that she'll give me more information when I’m at the police station.

- I agree at first, but the more I think about it the weirder it seems, so I contact her again to ask for a written notice requiring my attendance. I’m thinking of the previous notices I'd received from the police: on those letters, they'd specified whether an investigation had been opened, and stated the relevant law. I hope that, by getting a written notice, I'd get a few more clues about what this whole thing was about. But the letter, when I receive it, merely re-states the appointment time we'd agreed upon, with no other information.

- I email the police officer back, stating that, as far as I can see, there is no actual investigation and my attendance is not compulsory, since the letter doesn't allude to any law that would require me to present myself before the officer. I ask the officer to correct me if I'm wrong about this. At this point, I still don't know what this is all about.

- The police officer neither confirms nor corrects what I stated in my email. She just reiterates our appointment time. I still have no clue WTF is going on.

- I write back asking how long it'll take. The police officer says it'll be less than an hour. I still don't know what it's about. And a lot can happen in an hour, right? You could get arrested in under an hour.

What would you think? What would you do?

In 2017, while some friends and I were under investigation for an alleged Public Order Act offence — i.e. we participated in a vigil outside the prison ahead of an execution — some of our group were stopped at the border when they tried to leave the country. They hadn't been arrested or charged with any offence, and there was no warning that anything like that would happen. Getting blocked at the border caused inconvenience, anxiety and distress. I can only assume that, had I also tried to leave the country before I'd been questioned for that investigation, I would also have been stopped.

This was a scenario that ran through my mind as I considered whether I should comply with the request to go to the police station, or at least postpone the appointment. At that point in time, I had a few trips abroad planned: two conferences and a long-awaited trip to Scotland to stay with my in-laws. I didn't want to jeopardise those plans. Even if the police didn't seem to be exercising any legal powers to compel my presence, I couldn't be sure that this scenario was completely ruled out. I ended up going to the police station as scheduled, because I hoped to get whatever it was out of the way as quickly as possible. I even explained to friends at the time that I'd chosen not to delay the appointment because, if the police did something like confiscate my passport, I'd need enough time to find a lawyer and apply to the court to get it back.

During the hearing, the state counsel from the AGC said that it was “unfair” to claim that the police had pressured me in an unacceptable way. He reiterated that it was not in dispute that the police did not have the power to legally compel my attendance at the police station — although it was also the AGC's position that it'd been “necessary” for me to pick up the warning at the police station. The state counsel said that it hadn't been explained to me what would happen if I didn't attend, because I'd never asked. He questioned why I hadn't told the police about my travel plans or asked directly what would happen if I didn't show.

He even said that I'd never said anything along the lines of “I refuse to turn up until I am compelled, do what you can.” Because, apparently, in the eyes of the state, that is a totally normal and rational thing for a citizen to say to a police officer, in a situation where the individual still doesn't know what the matter is, and therefore has no real way of gauging how things might escalate with such a response.

I guess I should learn to say this in the future?

What about the point about how I'd been issued a conditional warning that didn't explain which part of my Facebook post had been in contempt of court? When I tried to get answers from the police officer in person, she would only tell me that “the post” was in contempt of court. When I asked if I could challenge the warning, she told me that I could write in to the police, and they would channel the matter to the AGC. It didn't exactly fill me with confidence; if I couldn't even get a straight answer while physically in the police station, I wasn't convinced that I would get clarity via email.

During the hearing, the state counsel said they didn't believe that this was a “genuine concern” on my part. He said that the contempt in my post was “quite obvious”, and that, since I am an “experienced journalist”, they found it hard to believe that I wouldn't know what the problem was. (In any case, their general position was that there is no obligation for such an explanation to be given.) It would have been “the easiest thing to do”, he said, for me to have emailed them if I really didn't know what was in contempt. (To which my lawyer pointed out that the “easiest thing” would have been to set out the explanation in the warning, or for the police officer to answer my questions when I asked at the police station.)

The judge did not address this point in the judgment. This is probably because he'd found that the conditional warning had no legal effect, and therefore could not be subject to judicial review, making the whole thing moot anyway.

According to Justice Kwek, a conditional warning has no legal effect and isn't binding because “it is only an expression of the authority’s opinion coupled with a statement of intent.” He also found that the 12-month conditional warning “simply conveys AGC's decision to proceed with a warning instead of instituting proceedings. That does not extend to AGC making an assurance to Ms Han that it would not prosecute her for the conduct that is the subject of the Warning, if she remains crime-free for 12 months.”

What I understand from this is that, even if I comply with the AGC’s stipulated 12-month “crime-free” period, if they wanted to they could still decide to prosecute me for contempt of court over the Facebook post anyway.

Great.

The power dynamics in this situation should have been clear: I am a citizen, and I was dealing with an officer from the Singapore Police Force, acting on a request from the Attorney-General's Chambers, a legal representative of the state. The police told me that there was an issue, but wouldn't give me any more information over the phone or email, and said they could only explain in person. So my only option, if I wanted to resolve the matter, was to show up at the police station as they wanted me to do. I might not have been legally compelled to go in, but the circumstances were such that I didn't realistically have any other choice.

It feels like my lived experience didn't matter during the legal proceedings. And it felt like the state lay blame for other aspects of my experience at my door: instead of addressing why the police couldn't have just told me what the issue was, it was my problem for not asking what the repercussions of a no-show would be, it was my problem for not flagging my worries with a police officer calling me to the station for unclear purposes, it was my problem for not writing in with my queries even after the police had failed to answer my questions in person, it was expected that I should have known what the problem with the Facebook post was because of my job. Why should the onus be on ordinary citizens to cover all the bases, instead of being on those in positions of authority to be clear and ensure that they aren't causing unnecessary inconvenience and distress? Why is it that, again and again in Singapore, those with less power are accountable to the state for their actions, and not the other way 'round?

This case is now closed — the only thing left to settle is how many thousands of dollars in costs I'll be paying the AGC.

How maddening.