When they visit him in Changi Prison, Nazeri bin Lajim’s loved ones aren’t supposed to be sad or talk about sad things.

Whenever I ask his younger sister, Nazira Lajim Hertslet, how he is, she describes him simply as “happy”. There’s no way for any of us to know if that’s how he really feels, but it’s a reflection of how he wants to make use of the limited time he has with his family. Death row prisoners are only allowed one visit (not more than an hour) each week; when family members are busy with jobs and other obligations, they might only be able to visit once every fortnight or month. Nazeri’s son, for instance, can only see his father when visitation days (either on Saturdays or Mondays) coincide with days off from his restaurant manager job. Every moment is precious, and Nazeri doesn’t want to waste any of it on tears and depression. I don’t want to talk about sad things, he tells his visitors. If you are coming to see me, you be happy.

Outside of prison, it’s obvious that Nazira is anything but “happy”. For many years she'd not really visited her brother in prison because seeing him incarcerated upset her, but she'd started going to see him regularly again once she realised that his life was in the balance, trying to make up for lost time.

She’s glad that her brother is staying positive, but is also acutely aware of how dire his situation is. When we sit and talk, words burst out of her, recounting old memories and expressing pent-up feelings of love, regret, heartache, guilt, pain, grief and rage. What she says about her beloved brother tells a story — of a life marked by drug use, incarceration and, ultimately, the harshest punishment — not often heard in Singapore, where a pro-death penalty, tough-on-drugs narrative dominates.

From privilege to deprivation

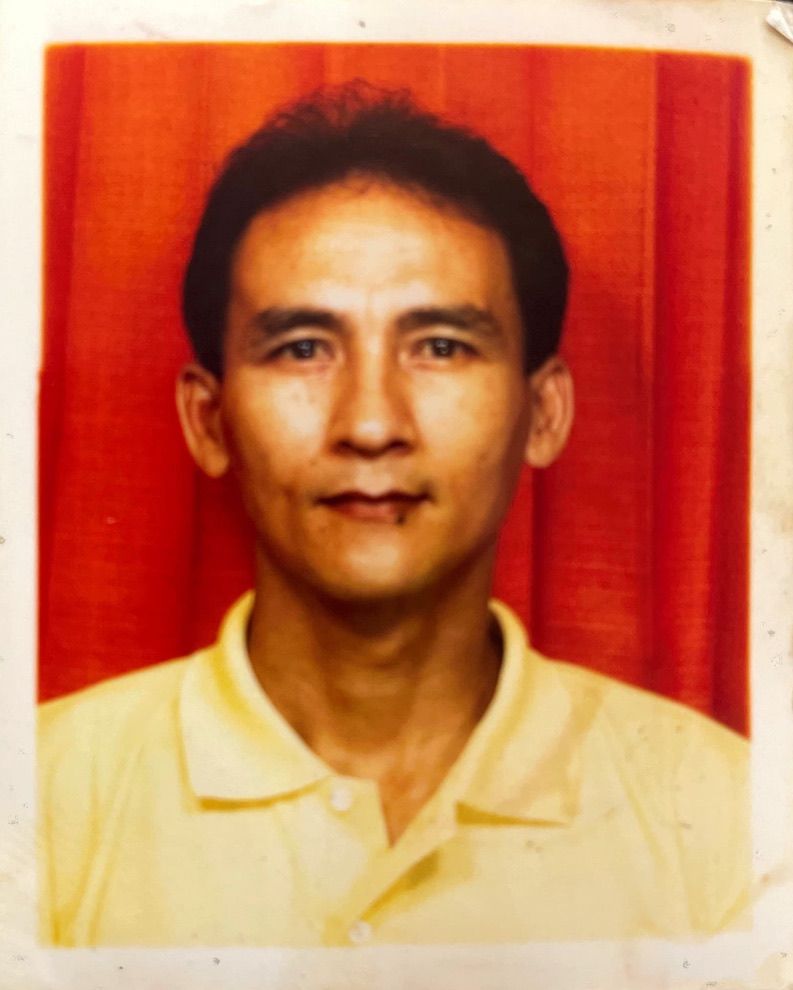

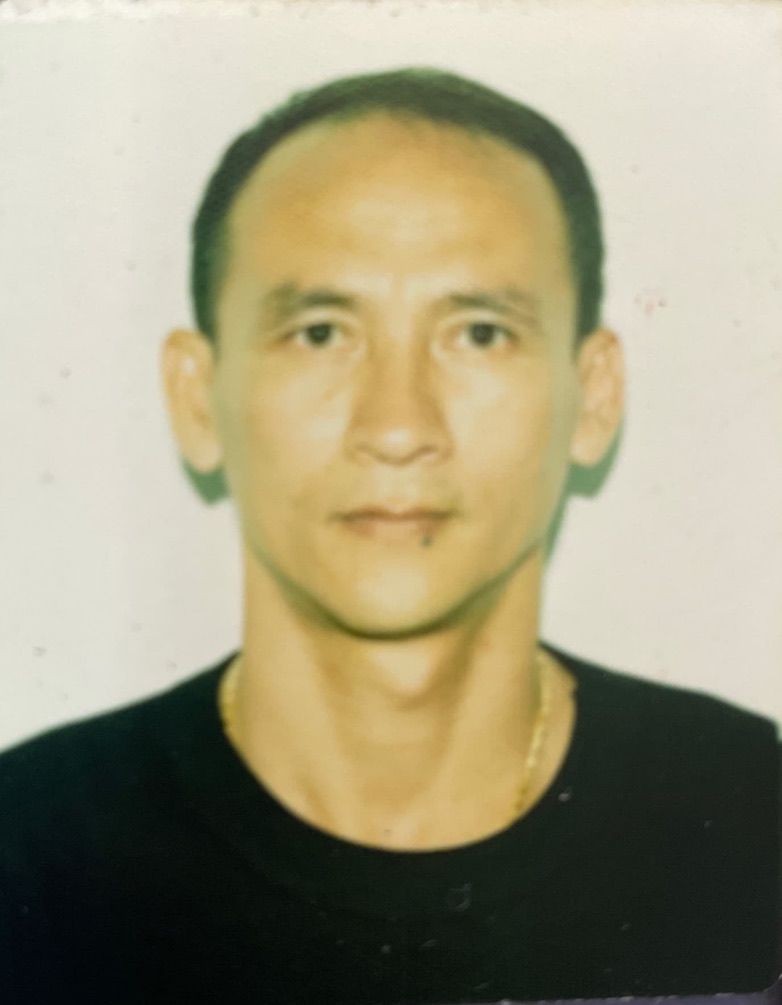

When I visit Nazira at home on a Friday night in May, she tells me that Nazeri is her favourite brother. He reminds her of their late father. There’s a physical resemblance, and Nazeri is as soft-spoken as his dad. “I guess that’s one of the reasons why I love him so much,” Nazira says. “Whenever I see him I feel like I saw my father.”

Born to an English father and Malay mother, their father had stuck out in the neighbourhood they lived in; he was six-feet tall, towering over everyone else, and had to get his shoes custom made because his feet were so much bigger than the standard. He was an administrator in the British Army, and was paid a sum considered kingly at the time. The family had a car and a television — all great luxuries. Life was going well, until the British Army withdrew from Singapore in the 1970s, years earlier than they’d planned and announced.

It was like the rug had been pulled out from under the family’s feet. “My father was so shocked, because there were nine kids to support, my mum wasn’t working, she was a housewife… it was a shock to him, where to get a job.” He was offered an opportunity to relocate the entire family to London, where he could continue working for the military, but Nazira’s mother — who couldn’t speak English — refused to leave Singapore. He worked for the New Zealand army for awhile, since they were still maintaining a presence on the island, but that job fell through too. The family’s fortunes declined. Nazira’s father’s health deteriorated, and he had a stroke that left him unable to work. He died when she was 18 years old.

The family plunged from their comfortable life into extreme poverty. “We were very, very poor, extremely poor, at that time. We struggled, my family worked very hard,” Nazira recalls. Her mother, who’d been a housewife throughout her marriage, became a washerwoman, taking on multiple jobs at a time. Nazira left school after her O Levels and started working two jobs, taking on shifts as a waitress. “My mum used to tell us, ‘Go out and work, don’t stay at home.’ We were trained not to sit down at home doing nothing.”

Multiple jobs left little time for quality family time. Focused on ensuring that there was food on the table for the little ones, Nazira’s mother had no time for her older children. “We were like strays, you know?” Nazira said. “My mother didn’t [have time to] bother [with us] because my mother worked very hard. Then the family became disintegrated.”

Nazeri was hardly home. From the way Nazira describes it, there wasn’t very much to return home to: “There [was] no love in the family. My mum used to beat him... I remember those days, he kena whack by my eldest brother.... I mean it’s so sad lah, our upbringing... because of poverty, there’s no love, come back kena beat kena wallop, there’s no food on the table... it [was] so depressing at that time.” Her eyes fill with tears. “Frankly speaking, sometimes... I always pray that I [can] erase this out of my mind. Because it's a trauma for my family.”

To escape this, Nazeri stayed away, choosing to spend time with his friends instead. It wasn’t clear to any of the family what he got up to. They only found out that he had developed an addiction to drugs when he got caught. It turned out that he’d been using drugs since he was 14 years old.

Singapore’s “zero tolerance” for drugs

Nazeri began his drug use at a time when the Singapore government was growing more determined to stamp drugs out on the island. In 1973 — a year after a teenage Nazeri started using methaqualone, known as Quaaludes in the US but referred to in 1970s Singapore as MX pills — Parliament passed the Misuse of Drugs Act, which consolidated the Dangerous Drugs Act 1951 and the Drugs (Prevention of Misuse) Act 1969, and set out a harsher stance against drug offences. “[We] have here some quite big-time traffickers and their pedlars moving around the Republic selling their evil goods and corrupting the lives of all those who succumb to them. They and their trade must be stopped. To do this effectively, heavy penalties have to be provided for trafficking,” declared then-Minister for Home Affairs, Chua Sian Chin, during the second reading of the Misuse of Drugs Bill in February 1973.

Under the Misuse of Drugs Act in 1973, trafficking a Class A drug like heroin or opium would attract a penalty of 20 years’ imprisonment, a $40,000 fine, or both, with 10 strokes of the cane added for good measure. But the legislation stopped short of capital punishment. As Chua said: “To act as an effective deterrent, the punishment provided for an offence of this nature must be decidedly heavy. We have, therefore, expressly provided minimum penalties and the rotan for trafficking. However, we have not gone as far as some countries which impose the death penalty for drug trafficking.”

Two years later, Chua had changed his tune. The stepped-up penalties in the Misuse of Drugs Act 1973, meant to act as a deterrence, had not worked. Instead, heroin use had shot up; according to Chua, the number of heroin users arrested had gone up 112 times in 12 months. The solution that Chua presented to this problem? Doubling down with even harsher punishments. This time, he argued for the death penalty for drug offences:

“A number of countries, including Malaysia, Thailand, Philippines, Burma, Egypt, Nigeria, Turkey and Iran, have imposed the death penalty for the unauthorised manufacturing, importing, exporting and trafficking of hard drugs such as morphine and heroin. The death penalty provided in the Second Schedule of the Bill is a close parallel to the provisions in the Iranian law in that the death penalty is imposed for the unauthorised manufacture of morphine and heroin irrespective of amounts involved, but in the case of unauthorised trafficking, importing and exporting of those drugs the death penalty is imposed only when the quantities exceed a specified weight.”

The death penalty for drug offences

Of the countries mentioned by Chua in 1975, only Malaysia, Singapore and Iran are still considered “high application” states when it comes to the death penalty for drugs. Egypt and Thailand are now classified as “low application” states, while Myanmar is a “symbolic application” state. The Philippines, Nigeria, and Turkey no longer have the death penalty for drug offences, even though thousands of people have lost their lives to extrajudicial killings in the Philippines’ high-profile war on drugs. You can find out more at Harm Reduction International’s 2021 report on the death penalty for drug offences.

A year before Parliament passed these amendments to the Misuse of Drugs Act, introducing the death penalty for drug offences, Nazeri had already made the switch from MX pills to heroin. He was only 16 years old.

“Sampah masyarakat”

Nazeri’s first arrest as a teenager marked the beginning of a lifetime of shuttling in and out of prison. Nazira estimates that her brother has spent three-quarters of his life trapped in this cycle of incarceration. Even as things got better for the rest of the family — Nazira puffs up with pride telling me how well her children, as well as nieces and nephews, are doing now, leading drastically different lifestyles from her own impoverished youth — Nazeri struggled.

“Among my family, he’s the one that [doesn’t have] good luck. Why? I think it's because of the addiction. He’s heavily [addicted to] drugs,” she says. "If not because of drug addiction, he’s a good person."

It’s something that frustrates her about her brother. Multiple stints behind bars, whether in state-run Drug Rehabilitation Centres or in prison, had not managed to stop his drug use. Even though he hadn’t had access to drugs while imprisoned, he’d relapse upon release. “I don’t understand what happened to him, why he succumbed to drugs after so many years inside. Why the minute he come out, he relapse.”

Nazeri isn’t alone in this. According to information provided by the Ministry of Home Affairs in response to a question in Parliament in August 2021, four-fifths of the penal population have been incarcerated before, the majority of them being repeat drug offenders. During a panel on drug use and drug policy that I’d moderated in December 2020, Dr Munidasa Winslow, a psychiatrist specialising in addiction and impulse control disorders, talked about how the lack of cravings for drugs while in a prison setting doesn’t necessarily indicate that one is completely cured of drug dependency. In such a structured environment, almost all decisions — from the time one wakes up in the morning to when meal-times should be — are made for prisoners; while the living conditions might not be pleasant, this release from the need to make big decisions and live up to messy obligations removes many real-world stressors from prison life. But things are different when one comes back out, and a multitude of burdens — from family expectations to concerns about employment and financial security — comes crashing down on one’s shoulders.

It's not just about illicit drugs

During the panel discussion, Dr Winslow also urged us not to get too hung up on officially reported recidivism rates for drug offences. Such rates only take into account illicit drug use, since the data is being collected from the point-of-view of law enforcement agencies concerned with drug offences and arrests. As long as someone stops using illicit drugs, they are counted as a ‘success story’. However, as a psychiatrist, Dr Winslow has seen people move off illegal drugs and on to other substances or behaviours, ranging from alcohol and (legal) sleeping pills to pornography and gambling. Basically, if the underlying issues that fuel an addiction aren’t addressed, the suffering and dysfunctional behaviour continues.

People who have been in prison have also described the experience as “dehumanising” and “humiliating”, designed to make someone feel low and bad about themselves. Nazeri showed signs of low self-esteem when he was out of prison. He’d tell Nazira that he felt that people looked down on him, and that he felt like “sampah masyarakat (trash of society)”.

As an introvert, he kept things close to his heart and didn’t talk much about his feelings. But Nazira is sure that the sense of societal rejection and scorn — of being seen as “sampah masyarakat” — ate away at him. “My brother is not a strong person. He cannot take criticism, he cannot take hardship, he cannot take all these things, he’s more soft-soft one,” she says. Once, when he was living with her after release, she’d taken issue with his relapsing into drug use. He picked up a knife and threatened to end his life if she were to kick him out of the house. “Naz, society looks down on me. I’m the worst person in society,” she remembers him telling her.

“I just went to the room and cried,” she says. “I [couldn’t] say anything. I [was] so helpless.”

Nazeri was eventually caught and sent back to prison again.

The capital case

As the years stretched into decades, Nazira watched this favourite brother going in and out of prison. But his last case escalated far beyond what she could have ever imagined as a worst case scenario.

In the early hours of 13 April 2012, Nazeri was arrested alongside Dominic Martin Fernandez, a young Malaysian in his 20s. Dominic had passed Nazeri two bundles, bound by black tape, which were found to contain “not less than 35.41 grams of diamorphine [heroin]”. In return, Nazeri had given him two envelopes containing $10,450. Both were eventually charged with trafficking 35.41g of heroin — above the 15g heroin threshold for the mandatory death penalty.

Nazeri did not deny that he’d intended to sell heroin — something that many people who are addicted to drugs do, to sustain their own consumption. What he argued in his defence was that he had only ordered one bundle of heroin, which he had planned to repack into smaller packets, some of which he’d keep for himself, while selling the others. According to Nazeri’s account of how much he would have kept for his own use, the remaining amount of heroin left for sale would have dropped below the threshold for the death penalty. He said he had no idea why Dominic had brought him two bundles.

However, his lawyer didn’t put this to Nazeri’s co-accused during cross-examination at the trial. Even though Dominic’s responses in court asserted that both bundles were meant for Nazeri, the trial judge observed that “[Nazeri’s] counsel appeared satisfied with [Dominic’s answers] and went no further even though they contradicted Nazeri’s account that he asked Dominic why there were two bundles.”

The judge also observed:

“Counsel also did not cross-examine Dominic on his recollection in paragraph 11 of his investigation statement that Nazeri told him before they met that he would be taking two bundles from him.

Counsel’s passivity extended to his examination of Nazeri. He did not tell him about what Dominic had stated and seek his response to it. One would expect that to be brought up if Nazeri did not agree with it.”

During the trial, Nazeri also claimed that he actually consumed more heroin than he’d stated in the statement he gave to the investigators. He alleged that he’d changed his statement upon the urging of the police, as they had not believed that he was such a heavy user. However, the judge noted that “those allegations were not put to the recording officer, interpreter or any other CNB officer during the trial.”

Ultimately, the trial judge did not buy Nazeri’s defence, ruling that he’d been the intended recipient of both bundles of drugs, and that his heroin consumption was what he’d stated in the police statement and not what he’d claimed in court. On this basis, the amount of heroin meant for sale exceeded the threshold for the mandatory death penalty. Nazeri was sentenced to death on 21 September 2017. Dominic, on the other hand, was found to have been merely a courier, and was also certified as having “rendered substantive assistance” to the Central Narcotics Bureau. He was given a life sentence and 15 strokes of the cane.

Nazeri’s appeal was dismissed in July 2018. In 2021, Nazeri — now represented by human rights lawyer M Ravi — filed a review application to the court, arguing that there had been new legal developments in the law, that a psychiatric report could prove his heavy use of heroin, and that his former defence lawyer had provided “inadequate legal assistance”. In response to that latter point, Nazeri’s former legal counsel, James Masih, wrote a letter that the ended:

“In Conclusion, I wish to say that I honestly did my best for the Applicant at the trial and at the Appeal. On hindsight I accept that I overlooked certain matters which could have helped the defence of the Applicant. I humbly leave the matter to the Honourable Court to make such orders as may be deemed appropriate on the application of Nazeri Bin Lajim.”

However, while noting Masih’s acknowledgement, the court did not find that he’d behaved in a way that “could be fairly described as flagrant or egregious incompetence or indifference”. They were also not persuaded by the other arguments presented, and ruled that there was not sufficient material to justify reopening the case.

Nazeri remains on death row.

A rejected pardon

The very first time I meet Nazira is at the Starbucks at Plaza Singapura; it’s a convenient landmark to meet before heading towards the Istana. She’d contacted me over WhatsApp, after we were put in touch by the family member of another prisoner on death row, asking what could be done for her brother. I’d suggested submitting an appeal to President Halimah Yacob to grant Nazeri a pardon and commute his death sentence to life imprisonment.

Frankly speaking, such appeals for mercy are a long, long shot. We now also know that while appeals are made to the President, it is in fact the Cabinet — made up of government ministers who defend capital punishment domestically and abroad — that decides on clemency petitions. Furthermore, the government’s legal advisor is the Attorney-General, who heads the state organ that prosecutes these offences and seeks the death penalty in these cases in the first place. No death row prisoner has been granted a pardon since 1998.

But still we go through the process every time, harbouring in our hearts a shimmering sliver of hope that this time might be different, that this time there will be mercy where before there had been none. When the situation is so desperate, even long shots are better than doing nothing at all.

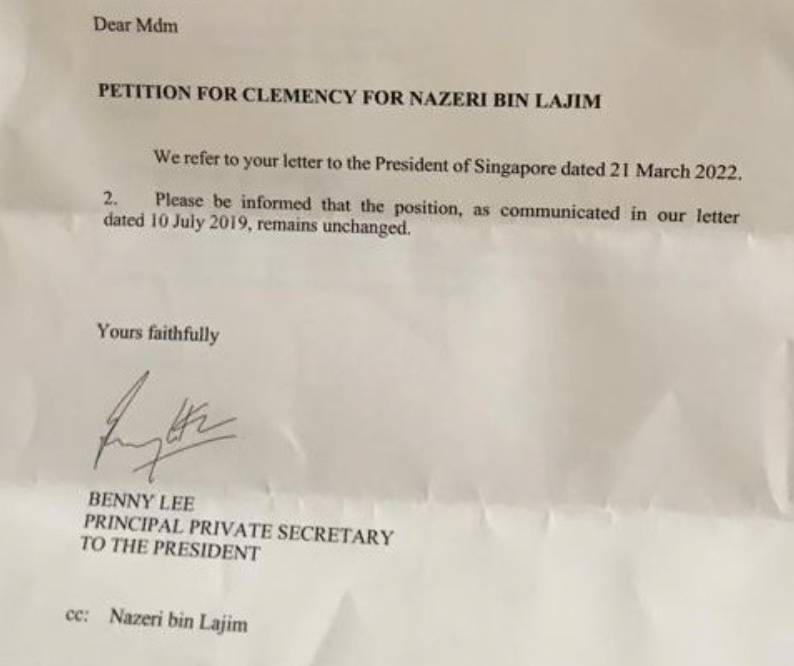

The response from the Istana came a month-and-a-half later. “We refer to your letter to the President of Singapore dated 21 March 2022. Please be informed that the position, as communicated in our letter dated 10 July 2019, remains unchanged,” the letter said. Attached to it was a copy of a letter, dated 10 July 2019, rejecting Nazeri’s original plea for mercy.

In his speeches in the 1970s, Chua Sian Chin, then the Minister for Home Affairs, emphasised the distinction between people addicted to drugs and those who trafficked illicit substances. He portrayed people who got “hooked” on drugs as victims whose lives would be destroyed, arguing that this made the traffickers who supplied them “the most abominable of human beings if he can be deemed ‘human’”. In 1975, he assured his fellow legislators that the introduction of the death penalty for drug offences would not lead to the inadvertent execution of consumers instead of traffickers. One group were victims to be protected, the other the “merchant of ‘living death’” to be killed.

Yet Nazeri’s life story — and that of Abdul Kahar bin Othman, who was executed in March this year — shows that reality is much more complex. Harsh “deterrent” policies hadn’t got him to stop using drugs, not when the abuse and trauma of being at home was pushing him to find outlets for his pain. Time spent in Drug Rehabilitation Centres — really just prison by another name — and prison not only failed to provide him the treatment and support needed to end his dependency on drugs, but also damaged his sense of self-worth and made it more difficult for him to rebuild his life upon release. As with many drug users, Nazeri’s long-term drug use pulled him further into the drug trade, turning him into a seller as well as a consumer. Now, after a lifetime of addiction, punishment and marginalisation, he is expected to pay with his life.

“Why don’t you catch the kingpin?”

When I speak to some family members of death row prisoners, they tell me that their loved ones are worried that the state might step up executions because a backlog is building up inside. There are, as far as we know, over 60 people on death row right now; the majority of them men, convicted of drug offences.

I don’t hear about this from Nazira, though, because she says Nazeri doesn’t talk to her about these things. Still, she keeps up with news about the death penalty in Singapore. She reads about the executions of Abdul Kahar and Nagaen, and sees in those hangings the horror that lies in wait for her brother.

When Nazira thinks about her brother’s fate, there are aspects of his case that keep coming back to haunt her. She can’t accept that while her brother is on death row, the man who delivered him the drugs isn’t. She says that Nazeri, too, had cooperated with the police, but hadn’t been certified as having rendered substantive assistance to investigators. It was also decided that Nazeri hadn’t merely been a courier, while his co-accused had, but Nazira can’t wrap her head around that. It doesn’t make sense to her that this is how the system weighs one life against another, and decides who lives and who dies.

“Can the government give me a concrete answer: a supplier committed a crime, same crime as the trafficker, what difference does it make?” she demands, her voice rising with her desperation and frustration. “[The co-accused] cooperate on what… Where to get the drug, who is the kingpin? Maybe to catch all the small-small fry, but the kingpin you don’t know. Can you catch the kingpin? I don’t think the [police] can catch them, only maybe you can just catch the other parties… in the same circle of friends.”

On Certificates of Cooperation or Substantive Assistance

Under Section 33B of the Misuse of Drugs Act, the prosecution can certify that an accused person has substantively cooperated with the Central Narcotics Bureau by providing information that’s used to disrupt drug trafficking activities. If this certificate is issued to someone who has also been found to have merely been a courier, the court can choose to sentence them to life in prison and caning, instead of death.

This system, however, grants a huge amount of discretion to the prosecution and the police, as they are the ones who get to say whether the information given is useful or has been used. In the case of Pannir Selvam Pranthaman, while it was acknowledged that he’d cooperated with investigators, the Central Narcotics Bureau claimed that the information he’d provided had already been known to them, and had therefore not been used in the arrest of a drug trafficker. Pannir was therefore not given a Certificate of Substantive Assistance and remains on death row.

Holding on to love and hope

I meet up with Nazira again a day after our interview, waiting for her outside the prison after she visits her brother. She says she’s told Nazeri about ongoing efforts to abolish the death penalty, assuring him that she’s trying her best to help him. But she’s also had to temper both his and her own expectations, because she knows how slim the chances are, now that he’s exhausted all his legal options and the clemency process.

“I told him, ‘I have to console myself. That [if you are executed] you’re going to a better place. Life here for you is so painful, you are moving [on] to a better place. So I have to console myself and you must console yourself, tell yourself that you’re going to a better place up there. Life is more better, then you can meet our mother and our father over there.’”

As she blinks her tears away, I think about what she’d said the night before, as our conversation stretched late into the night. She’d grown more meditative then, reflecting on everything that we’d been talking about. “At this stage, it’s a crucial stage, I have to do something about [Nazeri’s case],” she said. “I [am] partly to be blamed also. Had I been taking care of him more…” She rattled through a list of what-ifs: if she’d paid more attention, if she’d helped him more financially back when she had a job with a decent salary and year-end bonus, if she’d helped him start a small business that could have given him some financial security… Many years ago, when she’d visited him during one of his much earlier periods of imprisonment, he’d begged for help, crying that incarceration was torture. She hadn’t known what to do, and as a young woman leading her own life and shouldering her own responsibilities, hadn’t visited him in prison all that much.

“Why didn’t I [help him]? I keep asking why I didn’t do this. I should have done this for my brother, right? Why was I so self-centred [that] I never thought about that? Why didn’t I do this, why didn’t I do that? I keep blaming myself, I regret it so much. So much,” she said, her voice much quieter and sadder than the rapid-fire, no-nonsense tone she’d maintained earlier. “But I cannot turn the clock ‘round. I mean, it already happened… So now I want to pay off my guilt by helping him… because I didn’t help him last time. So I want to tell him I’m trying to help him. I’m making an effort now.”

While Singapore defines her brother solely as a drug trafficker, Nazira knows his struggles, his pain, his trauma. Where Singapore sees a criminal, she sees a favourite sibling whose face and body carry echoes of a beloved and much-missed father. As society spews scorn and judgement, she pays visits to her brother in prison, where he insists on laughter instead of tears.

There’s no indication of when the prison might decide to schedule Nazeri’s hanging. All Nazira can do is fight, as hard as she can for as long as she can. “I still think it’s very unfair. But overall I’m happy [that] he’s very positive. I said [to him], ‘I will never give up hope… I want you to know that we are doing something to help you out because I still believe in miracles.’”

Thank you for reading this story. Please feel free to share it far and wide.